Sustainable Living and the Patuyas of Naya

Shrutakirti Dutta

A scroll painter’s home in Naya, Midnapur, West Bengal

A chitrakar working on an “item”

When you enter the patuya para (scroll painters’ locality) of Naya, Pingla, a village in West Midnapur, you are met with a row of houses whose walls are brightly painted with images of plants, flowers, and animals. If you arrive in winter, at every turn you are likely to find an artist bent over an “item,” as it is pithily described by veteran chitrakars (also called patuyas, or scroll painters). This “item” could be an article of clothing or a piece of home decor on which they may be painting familiar motifs from scroll paintings. These will later take pride of place at kiosks and stalls in fairs across Bengal throughout the winter, fetching the chitrakars an increasingly large proportion of their annual income.

Dukhushyam Chitrakar

Take a right turn and you might meet Dukhushyam Chitrakar, a patuya for more than sixty years, out for his usual morning walk. More often than not, he will speak wistfully of a time when scroll painting was primarily an oral tradition where the song took precedence, in terms of both process and significance, over the artwork. Patuyas would travel from village to village, singing songs based on tales from Hindu epics and contemporary events. The long scrolls would be unfurled in conjunction with their song, visually tethering the narrative. Villagers would eagerly gather around a patuya to watch his performance. Afterwards they would pay him in kind, and sometimes with money. Having thus secured provisions for the day, the patuya would return to his community where, in the evenings, it was often customary to gather together and sing the familiar songs again; this time, informally, and offer criticism and suggestions to further hone their craft.

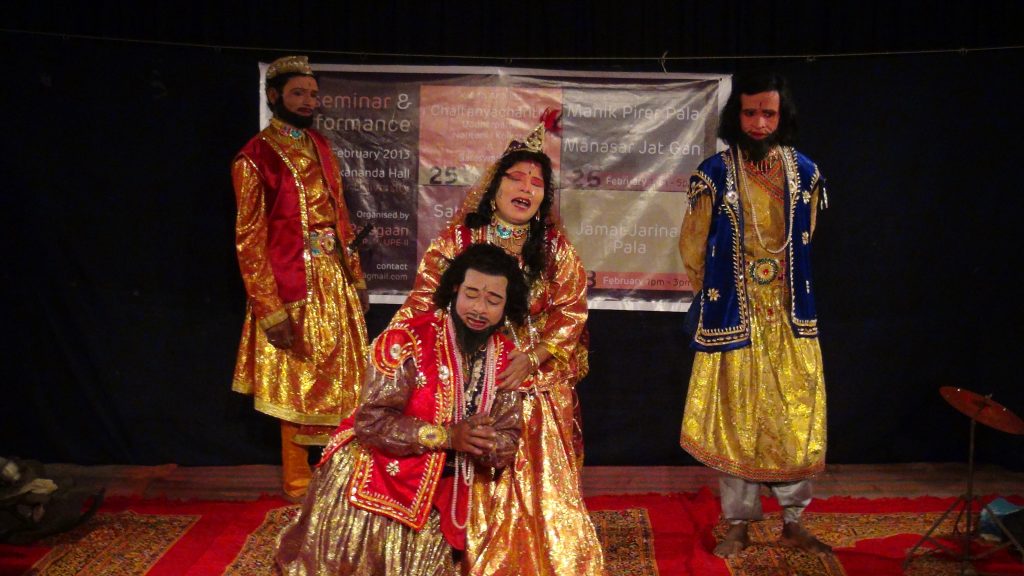

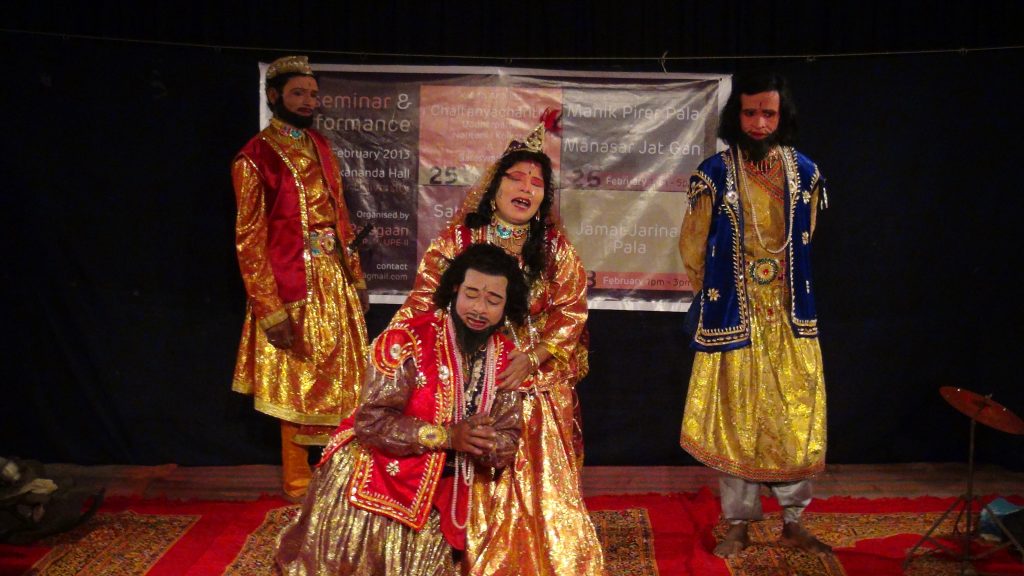

Traditional jatra Gunahabibi-r Pala performed by Diamond Harbour Group (Project Palagaan, 2013, Jadavpur University)

The picture Dukhushyam paints for us is one that has been disrupted by complex cultural changes in the cities and villages of Bengal. Over time, with the advent of radios and televisions, the demand for older performance traditions of jatra, pala, and pat-er gaan slowly diminished. Pat-er gaan (scroll songs) no longer remained one of the primary choices of entertainment among village residents, and thus ceased being an adequate means of livelihood for the patuya community. Over several decades, this translated to the loss of some songs and verses (payar) which died out from disuse and lack of intra-community exchange, as Beatrix Hauser shows.

Colour Making: A Sustainable Practice?

Documenting the making of natural colours in a Naya household

Patuya communities are spread across many villages of Bengal and face similar threats to their craft. However, being part of the Famine Tales team made me think about the impact of these changes in Naya, particularly on their colour-making tradition. By working outside the new commercial model, we wanted to see how far we could address the challenges that now arise while gathering the raw materials traditionally used to create a patachitra (scroll painting).

Raw white rice being ground into paste

Scroll painting traditions across greater Bengal were influenced by the topography, climate, and produce of the region, with colours and pigments made from easily sourced, widely available natural ingredients like grains, weed, flowers, fruits and vegetables. The style of patachitra varied greatly depending on the patuya’s location. Patuyas from Orissa, for instance, use minerals and stones to obtain pigment, such as ground conch shells to create a creamy white. In Midnapur, these raw materials are substituted with what is locally grown. Since paddy is the primary crop of Bengal, it makes perfect sense that the shell is replaced by raw, uncooked rice to produce the same colour.

An old handi (pot) being used to gather flame black

A shil nora (grindstone) being used for colour making

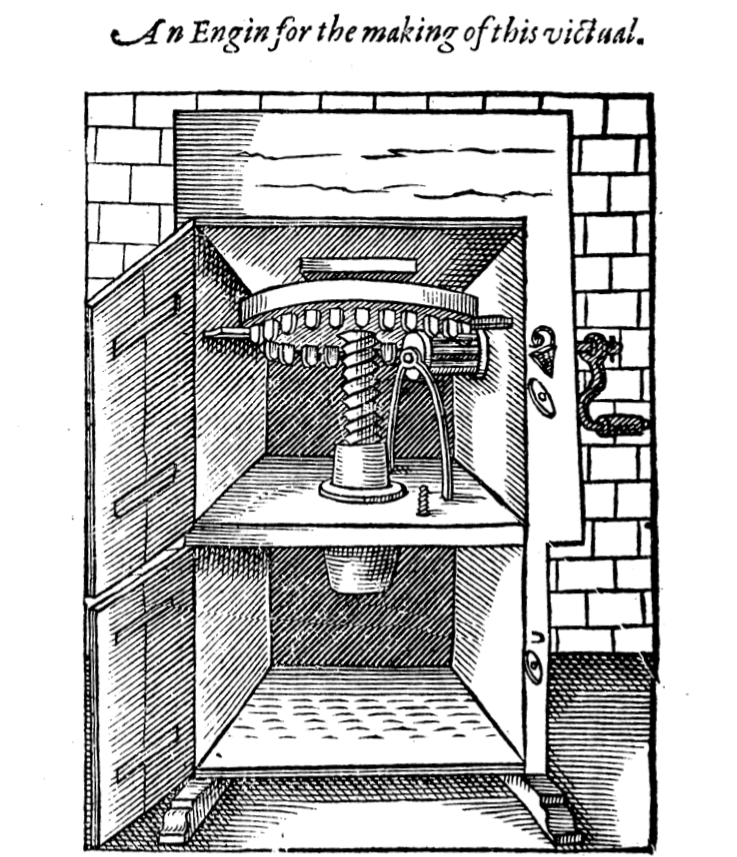

Due to the process itself, domestic and artistic spheres have been inextricably linked in the practice of scroll painting, and there exists a steady network of exchange between the two. The very tools used for the production of natural dye, the shil nora and the handi, come from the kitchens of the community.

Coconut shells containing colours made from tumeric, ground brick and burnt black rice

The vessel of choice to store the colour is an empty coconut shell, hollowed out and cleaned thoroughly after the fleshy interior has been eaten.

Dried bel (wood apple) stored for use as cooking fuel

A fundamental ingredient in natural colour-making is the wood apple or bel (Aegle marmelos) whose seeds, when mixed with water, yield a glue that acts as a temper for natural pigments and an organic disinfectant for the scroll. The use of this ingredient is a testament to the resourcefulness of the community who let no part of a raw material go to waste. Since only unripe fruit can be used for this process, the flesh of the wood apple is not fit for consumption after the extraction of glue. This results in a heap of discarded fruit which is left to dry in the sun to be used as cooking fuel later in the month.

Rehana Chitrakar and Lutfa Chitrakar engaged in colour making

Perhaps because the implements and ingredients used to make colour are rooted to traditionally gendered spaces, colour making within the community remains a process led by women. Patachitra is a living tradition, finding place within an active and demanding domestic structure, and thriving in it. Children of the chitrakar community learn to paint by observing their parents and engaging with the tradition from a very young age.

Mahima Chitrakar, eight years old, painting traditional fish motifs

An array of items painted with chemical colours, being sold at the annual Patmaya fair at Naya

Sustainable living has been a way of life with food insecure communities like the patuyas, who, by convention, never own land and cannot afford to grow the fruits and vegetables required in bulk for colour making. However, raw materials which, decades ago, may have been available for free (such as a neighbour’s excess produce of bel) today require money to purchase. Dukhushyam speaks of a time when he and fellow patuyas would simply walk to a nearby forest and forage for the things they needed. Regional ecologies have altered, these forests no longer exist, and therefore neither does this harmonious chain of supply. Several colours have retired from the palettes of patuyas because their source ingredients like tela kucho (below left) can rarely be found today, or like bhushum mati (below right) is available for an increasingly small window in a year.

Left: Tela kucho (coccinia grandis); Right: Bhushum mati (local name for soil extracted by digging 8-10 feet under dried sweet water ponds)

Today patachitra made from natural colours have become something of a novelty, usually made when specifically commissioned. Time and cost-effective alternatives like chemical colours have gained popularity among patuyas over time, although this has come at some cost to the living tradition.

Solutions: Past and Present

Interventions have been made since the last century to protect the art form and empower the community of patuyas. Between 1929-40, during the surge of the nationalist movement in Bengal, Gurusaday Dutt – a civil servant in British India – collected various “folk” artefacts from across rural Bengal, including patachitra, with the intention of preserving indigenous art forms and living traditions. Today this considerable collection resides at the Gurusaday Museum in Calcutta.

There was renewed interest in patachitra in the 1960s and 70s among the urban intelligentsia of Calcutta. Artists Hiran Mitra and Ganesh Haloi supported patuyas in their personal capacity, and the poet Dipak Majumdar commissioned several scroll paintings and brought the community wider recognition. Professor Sankar Sengupta organized the first All India Folklore Conference in 1964. These interventions brought patachitra back into the conversation. While the stories from the Mangal Kavyas, or the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, were considered significant for their historic value, they no longer served as ubiquitous “entertainment”.

The West Bengal government-led annual Hasta Shilpa Mela (handicrafts fair) and Biswa Bangla have provided platforms to generate revenue streams for rural artists. The Rural Craft and Cultural Hub (RCCH) project has been an ongoing initiative to provide some agency and relief to Bengal’s indigenous craft communities, like the patuyas.

Potmaya 2019 – a patachitra festival

Since 2010, a Kolkata based NGO’s Art for Life initiative has facilitated the income of patuyas in Naya by establishing an annual patachitra mela where patuyas can market their skills and sell their craft to a wider network of buyers. During my visit to the fair in November 2019, I observed pat-er gaan (scroll songs) being sung from kiosks at various intervals, drawing the audience towards a particular table and its wares. For a brief moment, people gathered together to record the spectacle on their device of choice, before moving on to inspect a t-shirt or set of coasters. Within this context, shorter narratives have gained favour over those depicting more sophisticated storylines. Now pat-er gaan needs to be truncated and/or abridged to better hold the audience’s attention. Finer details within the artwork and the intricacies of parallel sub plots within the narrative are omitted in favour of straightforward, shorter stories.

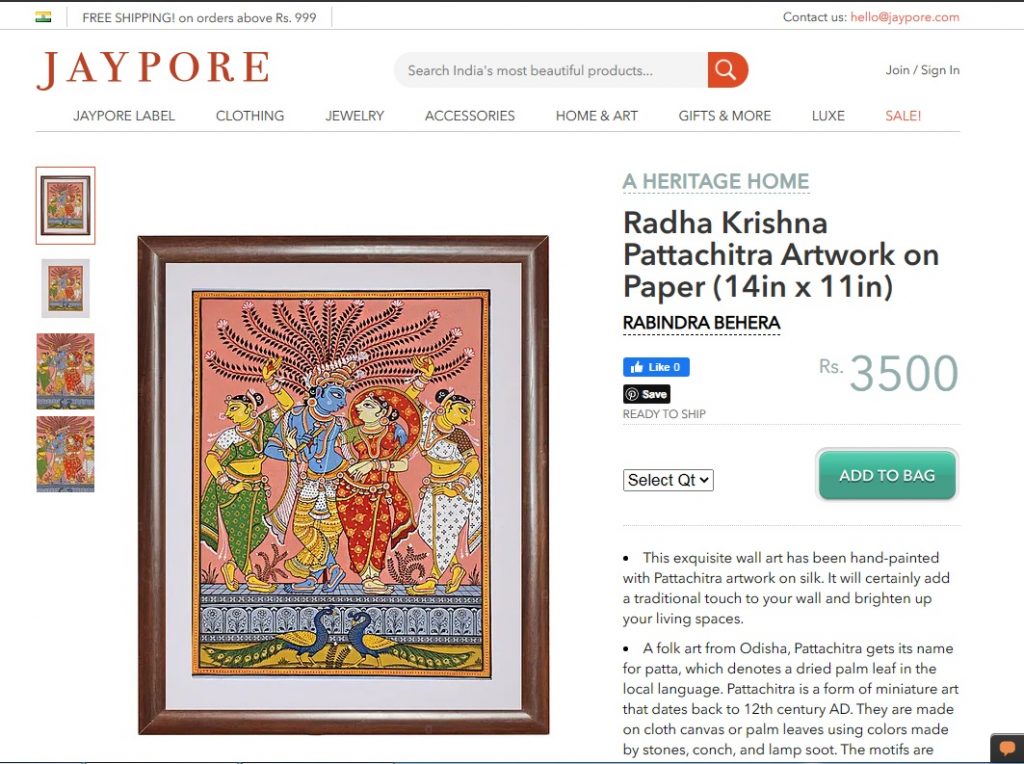

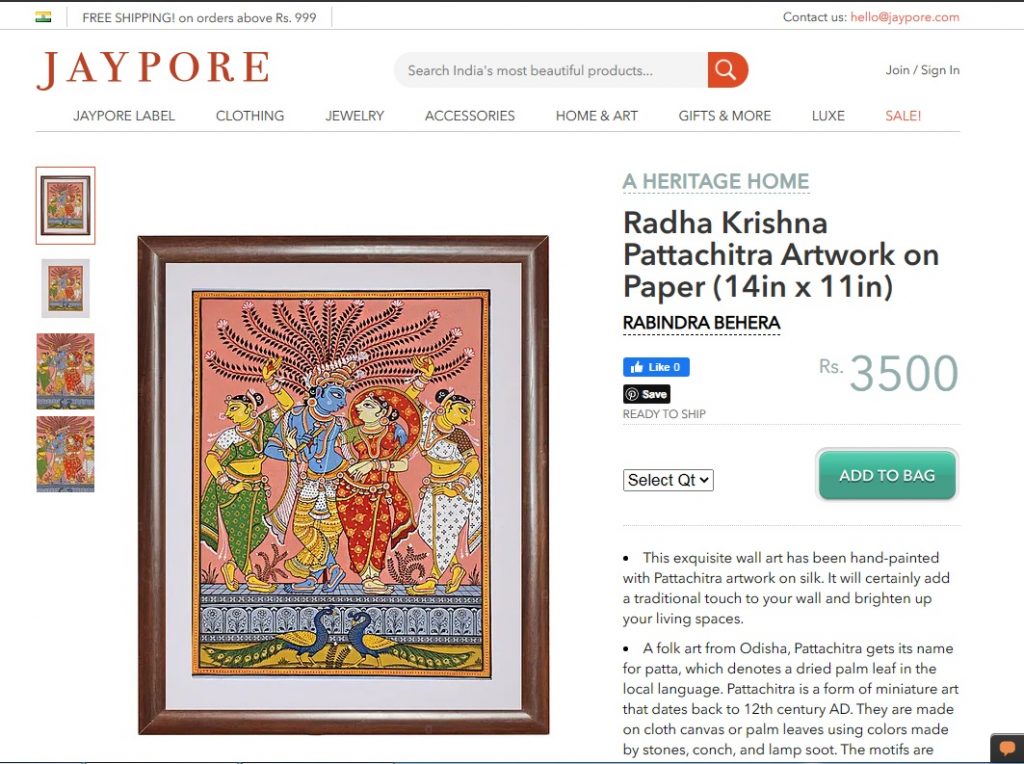

Website selling patachitra for display in modern homes

Changing market structures have thus influenced and altered the process of scroll painting itself. Public access to patachitra has come via fairs, which became the primary site for patuyas to showcase and sell their scrolls. The focus shifted from the oral storytelling aspect of the patachitra tradition to the two-dimensional visual art form, dismantling the core structure of scroll making and altering the thrust of the living tradition. Patachitra entered Bengali living rooms and stayed there as framed pieces of art.

The motifs painted on the “items” are taken directly from traditional scrolls but presented without narrative or context. The very medium which gave patachitra its name – patta or cloth – has altered and expanded to include various media, such as wood, steel, copper and terracotta; eventually, turning patachitra into “items” for sale (Potmaya news report 2019 ABP). While these initiatives have contributed substantially towards the chitrakars’ visibility and financial security, the paradigm shift in the perception and consumption of indigenous craft traditions like patachitra, the impact on local ecology, sustainable living, land-ownership and tenure issues among patuyas, and the breakdown of local organic economies, remain largely unaddressed.

Steps have been taken to encourage and preserve older traditions of patachitra in sustainable ways. The Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Kharagpur, whose campus is located a few miles from Naya, distributed saplings of specific flower-bearing plants to the patuyas to sustain the use of natural ingredients in making colours and pigments. One such example was the Latkan or Achiote.

Latkan, or Achiote seed, produces a gorgeous liquid red

The seeds of this fruit yield a fiery, liquid red colour when pressed in the palm of one’s hand. This ingredient and the hue produced from it has proved overwhelmingly popular among the chitrakars and feature in almost all of their paintings. Yet, access to the fruit still remains difficult for the chitrakar community. Dukhushyam and his family either have to depend on the generosity of landowning neighbours who can afford to plant the sapling, or make a trip to the IIT campus to source the raw ingredient themselves. However well-intentioned, modern measures designed to address the economic prosperity of the patuyas, or the availability of specific natural ingredients, have their limitations when it comes to addressing the wider ecological issues that impact the survival of a community like Naya.

With this in mind, organisations and institutions have paid specific attention to the uniqueness of patachitra‘s oral tradition. Applying the storytelling potential of pat-er gaan, projects like HIV scrolls, or initiatives focused on gender like Singing Pictures, and self-empowerment programmes (see: Malini Bhattacharya, Patua Art and Women Patuas of Medinipur, 2004), have commissioned patuyas to write songs and tell stories relevant to their projects. Sujit Kumar Mandal’s book Patuya Sangeet (2011) recovered in detail the immense and valuable corpus of patuya Dukhushyam Chitrakar, and documented colour making processes at Naya. More recently, our own Famine Tales project enables a team of patuyas, led by the legendary Dukhushyam, to create traditional scrolls with natural colours to reflect on food insecurity, an issue that continues to be germane to their own circumstances. Recent crises like the Coronavirus and the cyclone Amphan have shown exactly how vulnerable the community still is. Our endeavours can rejuvenate traditional methods of painting and mechanisms of sustainable living, and protect a community from an immediate crisis. But they cannot give patuyas adequate land to grow their ingredients, or provide longterm solutions to the larger, structural problems that underpin their continued food insecurity.

Dukhushyam’s reminiscences point to a patachitra tradition that existed in a delicate balance of ecological and social harmony, where the patuya community was integrated with a society that facilitated the art form, recognizing that doing so was part of their ethical and moral function. Cultural shifts in the cities and villages of Bengal have resulted in changes to the living tradition and ecological balance in the community, which cannot be resolved through economic intervention alone – hence Dukhushyam’s intuitive rejection of “item” making. The core practices of patachitra and pat-er gaan will continue to remain vulnerable until we as an audience collectively embody the shift we wish to see, making the journey from being mere observers who document Bengal’s endangered “folk” traditions, to facilitators who foster a community where living traditions can be integrated into modern life on their own terms.

Shrutakirti Dutta is a PhD researcher in the Department of English, Jadavpur University, Kolkata, and Research Fellow on the Famine Tales project. Her PhD project is titled “A Stitch in Time: Exploring Domestic Craft Practices in Nineteenth Century Bengal”.