Sir Hugh Platt’s Pasta

Ayesha Mukherjee

Quite unlike the ingenious culinary experiments undertaken by many during lockdown, I was hurriedly making my mundane mess of pasta last week, when I remembered the Elizabethan scientist Sir Hugh Platt’s recipes for “macaroni”. Ubiquitous, unremarkable, standardised and sold in convenient packaging though it may be in our time, pasta was a tantalising promise in early modern England.

Hugh Platt’s famine remedies, written “vppon thoccasion of this present Dearth”. Copy at British Library, London.

Especially so in the 1590s, when the country faced one of its most acute food crises. The harvest failed repeatedly, the price of wheat soared, as did prices of barley, oats, and other food. The regions of the north and midlands were worst off, and the poor began to migrate London-wards. Hugh Platt experimented diligently to find what he called “remedies against famine” – mostly, coping mechanisms, making things last, finding substitutes, recycling, waste-reductive measures, and so on. He published some of these in his manual Sundrie new and Artificiall remedies against Famine in 1596, which was the third successive year of harvest failure. Among other things, this book contained many experiments with bread substitutes and various staple foods. Ways were sought to eliminate the “ranke and vnsauorie [unsavoury]” taste of peas, beans, beechmast, chestnuts, acorns, and vetches, so that these might be used instead of wheat flour. Bread was also made with “pompions” [pumpkins], cakes with parsnips, measures were devised to prevent mills from wasting flour while grinding, and much more ….

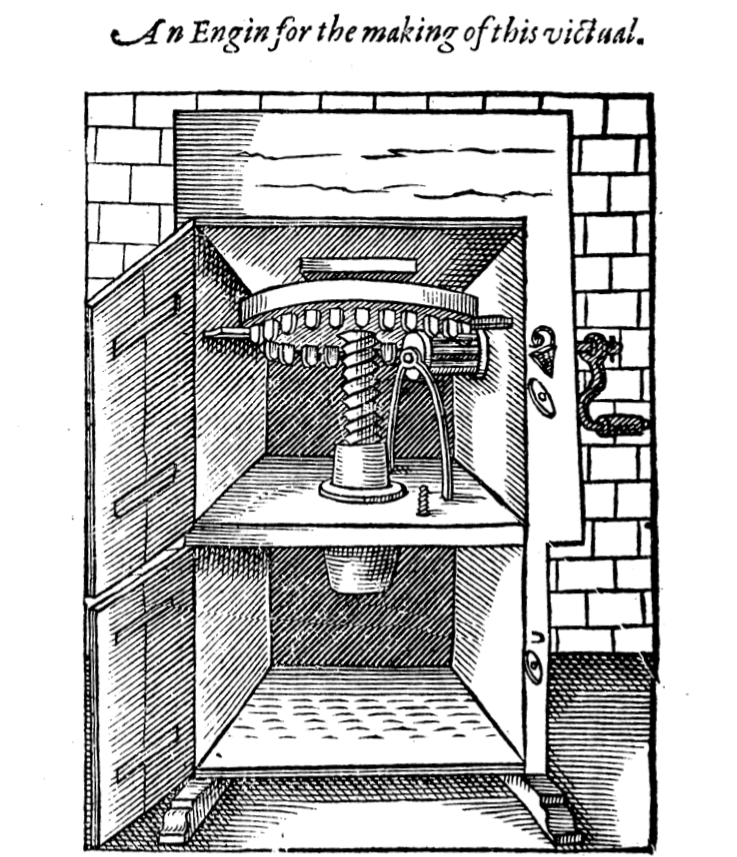

What could one eat in such times that was affordable and easy to preserve, wondered Platt. In his astonishing collection of experiments and recipes called The Jewell House of Art and Nature, published in 1594, when the food shortages of the decade had just begun, he had tempted his readers with the promise of “A wholesome, lasting, and fresh victual for the Nauie [Navy]”. He pointed out, with characteristic pragmatism, that when corn sold for 20 shillings per quarter, 8 ounces of this new food could be had for a penny to make “a competent meale for any reasonable stomach”. It was magically cheap and lightweight, shaped like “wafers”, and could be dressed to serve “both for bread and meat”. In his current context of food shortage, Platt was keen for this food to be eaten in households, not just by seafarers. So he boldly served pasta (as we may now call it) at his own table. It appears to have gone down rather well. For he even designed a pasta machine and printed its illustration: an “Engin for the making of this victual”.

Macaroni machine illustrated in Hugh Platt, The Jewell house of Arte and Nature (1594), p.75.

Sir Hugh Platt’s manuscripts record his repeated experiments (some dated December 1595) before he got his pasta quite as perfect as he wanted it to be. He tried to make it more nourishing, and of better taste. The flour was kneaded with aniseed, liquorice, and ginger, or boiled milk, or eggs – depending on what was available. To make it last, he tried adding aqua composita (alcoholic flavoured water), cinnamon, and wine or ale wort. Apparently, seething the macaroni in pudding skins made it tougher, and the paste of flour was driven through hollow pipes and dried. The manuscripts with these experimental recipes are preserved in the British Library’s Sloane collection. I cannot imagine how pasta laced with aniseed or liquorice might appeal to the palate … but the material sense of taste is perhaps as contextually driven as the recipes and ingredients themselves, and the eaters of Hugh Platt’s pasta may have tasted it differently.

In Platt’s collection of food and drink recipes for sailors, printed in 1607, a year before his death, he described a “cheap, fresh, and lasting victuall, called by the name of Macaroni amongst the Italians,” which seemed useful at a time of shortage.

From Platt’s broadside, Certaine philosophical preparations of foode and beverage for sea-men, in their long voyages (1607). Copy at British Library, London.

Platt had furnished the famous explorers Sir Francis Drake and Sir John Hawkins with his macaroni, since it was long-lasting and helped to address shortage of staple food aboard ships during long voyages.

In the difficult decade of the 1590s, pasta had a strange renaissance in England – it metamorphosed from a foreign curiosity consumed by sailors to a domestic food, enough for “a reasonable stomach” in times of dearth, and then, an item locally (and perhaps mechanically) manufactured and supplied to English sailors for survival.

I’m not quite sure what remedies Hugh Platt would have recommended for this ….

“Pasta sold out at Tesco, Finchley, London”, during the Covid crisis, March 2020. Wikimedia Commons. Philafrenzy / CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)

Ayesha Mukherjee is Associate Professor of Early Modern Literature and Culture in the Department of English, College of Humanities, University of Exeter. Her book on Hugh Platt and the 1590s food crisis in England is called Penury into Plenty: Dearth and the Making of Knowledge in Early Modern England (2015) and she is the Principal Investigator for the AHRC projects Famine and Dearth in India and Britain, 1550-1800 and Famine Tales from India and Britain.