“Food security” doesn’t immediately signal work done in humanities disciplines. It is a complex, contested issue, whose currency and significance are hardly debatable given present concerns about environmental change, resource management, and sustainability. It’s largely studied within science and social science disciplines in current or very recent historical contexts. And yet, the concern about long-term availability, quality, and distribution of food has a history that can be traced far back. This isn’t only a history of economics and agricultural or technological development; it’s equally a history of human responses, resilience, and representations. Food security has a social and cultural history of considerable ethical value. This blog invites people to communicate this to a wider audience.

Food Security: Past and Present is part of a research project in the humanities which looks at food security from an early modern perspective (sixteenth to eighteenth centuries). Geographically and culturally, it compares attitudes towards the concern in India and Britain. Food, famine, and dearth are not issues that are, or have been, problematic for the “Third World” alone. The Western world too has a long history of coping with food crises. Hence the comparative approach of our project.

“What’s the use?”

When I described the project to a friend who does not work within a humanities discipline, she said, “But what’s the use? The phrase ‘food security’ didn’t even exist in those days.” True, even if the point is put in a manner that may rile humanities scholars who professionally invest in recovering the past, and to whom the “uses” of the past may be self-evident. Rather like the words “sustainability”, or “climate change”, “food security” is a recognisably contemporary term. If we want to apply the past to the understanding of urgent present concerns, we will have to address questions like the above in an accessible way. A fundamental point to make, perhaps, is that ideas and concerns can pre-date phrases and terms, and can also develop beyond the moment at which a particular terminology is invented. In other words, the phrase “food security” may not have existed in, say, sixteenth-century Britain or India, but concerns about long-term food availability, access, and health did. People came up with ideas for addressing these issues and argued about them. Many of these arguments are relevant today, as are questions of public knowledge and dissemination.

An early modern example

![Soc[1].Ant 1](http://foodsecurity.exeter.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Soc1.Ant-1-153x300.jpg) In the last decade of the sixteenth century, England faced a notorious food crisis, after four consecutive failures of the wheat harvest (1594-97) and rises in food prices. In these difficult times, a scientist, medical practitioner, trader, poet, and socio-economic analyst Sir Hugh Platt began to publish experiments for “remedying famine”, which he had conducted since the 1580s. The latter half of this century, in fact, saw some of the most serious food shortages recorded in early modern England – 1555-57, 1586-88, and finally, 1594-98. Platt experimented with numerous ways of recycling, reducing waste in households and trades of his time, balancing trade or business interests with environmental concerns, improving agricultural techniques and practices, soil analysis and use, land management, food production, preservation and transport.

In the last decade of the sixteenth century, England faced a notorious food crisis, after four consecutive failures of the wheat harvest (1594-97) and rises in food prices. In these difficult times, a scientist, medical practitioner, trader, poet, and socio-economic analyst Sir Hugh Platt began to publish experiments for “remedying famine”, which he had conducted since the 1580s. The latter half of this century, in fact, saw some of the most serious food shortages recorded in early modern England – 1555-57, 1586-88, and finally, 1594-98. Platt experimented with numerous ways of recycling, reducing waste in households and trades of his time, balancing trade or business interests with environmental concerns, improving agricultural techniques and practices, soil analysis and use, land management, food production, preservation and transport.

He gathered ideas and practices from local people in London (where Platt himself was based) and beyond. His informants included not only landed gentlemen and aristocrats, but gardeners, farmers, apothecaries, carpenters, brewers, bakers, starch makers, goldsmiths, limners, dyers, soap boilers, saltpetre men, clothiers, medical practitioners, housewives, travellers, soldiers and sailors. In his experiments, Platt tested the practices of ordinary men and women of his day, modified or improved them, and published them for “public good” (“Bonum Publicum”). His work was printed in broadsides (a single large sheet of paper printed on one side – an early modern equivalent of a poster), pamphlets, and books. His first broadside appeared in 1593 (see excerpts), a year before the acute food crises of the 1590s began, and, until his death in 1608, Platt produced almost a publication per year. His work was reprinted and recycled throughout the seventeenth century, long after his death. He became something of a publishing phenomenon in his time. He was a great advocate of writing for people in “plain terms”, without learned jargon. Had he lived today, I’m convinced he would have, alongside his various activities, written a widely read blog! He deserves at the very least a separate blog post. That will appear in due course.

He gathered ideas and practices from local people in London (where Platt himself was based) and beyond. His informants included not only landed gentlemen and aristocrats, but gardeners, farmers, apothecaries, carpenters, brewers, bakers, starch makers, goldsmiths, limners, dyers, soap boilers, saltpetre men, clothiers, medical practitioners, housewives, travellers, soldiers and sailors. In his experiments, Platt tested the practices of ordinary men and women of his day, modified or improved them, and published them for “public good” (“Bonum Publicum”). His work was printed in broadsides (a single large sheet of paper printed on one side – an early modern equivalent of a poster), pamphlets, and books. His first broadside appeared in 1593 (see excerpts), a year before the acute food crises of the 1590s began, and, until his death in 1608, Platt produced almost a publication per year. His work was reprinted and recycled throughout the seventeenth century, long after his death. He became something of a publishing phenomenon in his time. He was a great advocate of writing for people in “plain terms”, without learned jargon. Had he lived today, I’m convinced he would have, alongside his various activities, written a widely read blog! He deserves at the very least a separate blog post. That will appear in due course.

Public awareness

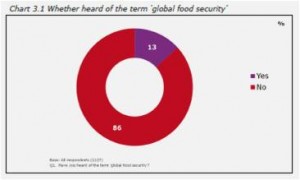

For now, it may be worth noting that Platt died anxious about the reception of his life’s work. In his last broadside, he worried whether his current and future socio-economic environments would allow his experiments, practices, and books to actually benefit the public. Would responsible ways of using the natural world and its resources ever become part of public knowledge and practice in the way he had envisaged? Or would “Nature’s cabinet of jewels” and its “secrets” remain closed to the public? One would think that with modern forms of knowledge dissemination, such worries should now be outdated. Yet, a 2012 survey of public attitudes in the UK towards food security, published by the Global Food Security Programme, revealed that 86% of the 1127 respondents, selected from across the country, had not heard of the term “global food security”, although 55% agreed they were more concerned about rising food prices than all other food issues.

For now, it may be worth noting that Platt died anxious about the reception of his life’s work. In his last broadside, he worried whether his current and future socio-economic environments would allow his experiments, practices, and books to actually benefit the public. Would responsible ways of using the natural world and its resources ever become part of public knowledge and practice in the way he had envisaged? Or would “Nature’s cabinet of jewels” and its “secrets” remain closed to the public? One would think that with modern forms of knowledge dissemination, such worries should now be outdated. Yet, a 2012 survey of public attitudes in the UK towards food security, published by the Global Food Security Programme, revealed that 86% of the 1127 respondents, selected from across the country, had not heard of the term “global food security”, although 55% agreed they were more concerned about rising food prices than all other food issues.

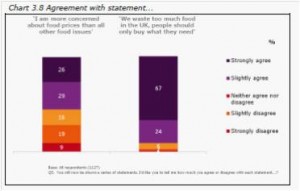

While 90% agreed with the statement that the UK wastes too much food and people should only buy what they need, 55% said that food security was not an issue that affected them but was more a problem for people in developing countries. The survey reflected that, in the wake of food price spikes in 2008 and 2011, people felt strongly about food prices and waste, but did not equate these issues with “food security”.

While 90% agreed with the statement that the UK wastes too much food and people should only buy what they need, 55% said that food security was not an issue that affected them but was more a problem for people in developing countries. The survey reflected that, in the wake of food price spikes in 2008 and 2011, people felt strongly about food prices and waste, but did not equate these issues with “food security”.

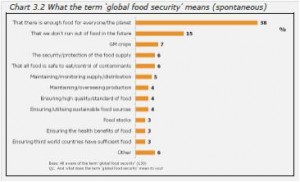

When the 14% who said they were aware of the term were asked to spontaneously describe what they thought it meant, most of them (38%) responded: “that there is enough food for everyone”. Very small proportions (3-6%) of the original 14% associated the term with safety, health, quality, distribution, or sustainability, which are fundamental aspects of the definition of “food security” as it has evolved over the last few decades, since the first World Food Conference of 1974. We may now possess the terminology, but not necessarily the wider awareness of its meaning, let alone of the debates or the history of human responses that underpin the term.

When the 14% who said they were aware of the term were asked to spontaneously describe what they thought it meant, most of them (38%) responded: “that there is enough food for everyone”. Very small proportions (3-6%) of the original 14% associated the term with safety, health, quality, distribution, or sustainability, which are fundamental aspects of the definition of “food security” as it has evolved over the last few decades, since the first World Food Conference of 1974. We may now possess the terminology, but not necessarily the wider awareness of its meaning, let alone of the debates or the history of human responses that underpin the term.

This is not for the lack of public concern or interest. Clearly, people who responded to this survey were concerned about food availability, price, and waste, particularly in local and national contexts. It is, rather, a gap in communication, and in the pragmatic and ethical tuning and coordination of current awareness, policy, and practice. The findings of humanities disciplines can help to address this gap. Human responses to famine and dearth in “the past” (pre-modern or pre-industrial worlds) can offer provoking examples to think with. This is because modern environmental crises have forced us to confront a relationship with famine that resembles its pre-modern counterpart. So, humanities scholars must communicate their findings beyond their immediate disciplines and coteries.

This is not for the lack of public concern or interest. Clearly, people who responded to this survey were concerned about food availability, price, and waste, particularly in local and national contexts. It is, rather, a gap in communication, and in the pragmatic and ethical tuning and coordination of current awareness, policy, and practice. The findings of humanities disciplines can help to address this gap. Human responses to famine and dearth in “the past” (pre-modern or pre-industrial worlds) can offer provoking examples to think with. This is because modern environmental crises have forced us to confront a relationship with famine that resembles its pre-modern counterpart. So, humanities scholars must communicate their findings beyond their immediate disciplines and coteries.

Sharing research

To this end, our workshop Food Security and the Environment in India and Britain brought together a group of literary scholars, historians, scientists, social scientists, and people engaged in community initiatives to discuss the interactive potential of their distinctive approaches to food security. The sessions kept the comparative approach of the project, looking at both India and Britain, and the chronology was extended beyond 1800. The sessions were thematically organised to enable comparison across time and place. Details can be found here: Workshop: Day 1 and Day 2.

To this end, our workshop Food Security and the Environment in India and Britain brought together a group of literary scholars, historians, scientists, social scientists, and people engaged in community initiatives to discuss the interactive potential of their distinctive approaches to food security. The sessions kept the comparative approach of the project, looking at both India and Britain, and the chronology was extended beyond 1800. The sessions were thematically organised to enable comparison across time and place. Details can be found here: Workshop: Day 1 and Day 2.

The Q&A after each session and the group discussions at the end of the day were rather vigorous and kept spilling across individual sessions – a good thing for any workshop. (Hugh Platt, who blended structure and method with formative, comparative dialogue in his experiments, would have approved!) We considered fundamental historical approaches to the topic of famine and dearth – through the lenses of social/moral economy, popular agency, and social order; economic history, evaluating “subsistence crises”; and climate change and “global” environmental crisis. We discussed ways of combining, modifying, or arguing with these approaches.

The Q&A after each session and the group discussions at the end of the day were rather vigorous and kept spilling across individual sessions – a good thing for any workshop. (Hugh Platt, who blended structure and method with formative, comparative dialogue in his experiments, would have approved!) We considered fundamental historical approaches to the topic of famine and dearth – through the lenses of social/moral economy, popular agency, and social order; economic history, evaluating “subsistence crises”; and climate change and “global” environmental crisis. We discussed ways of combining, modifying, or arguing with these approaches.

Many of the presentations attempted a synthesis, using evidence from literature and popular culture in different contexts within India and Britain. The history of human perception and representation is as vital as recovering data on individual crises. Local perspectives emerged as a particular priority – discussions of “global” crises can often displace local concerns in the human history of food security. How do we balance them? Geographical specifics, conditions of travel, networks of people, roads, and trades, ecologies and uses of rivers, popular idioms and landmarks, the agency of popular protest against state-led measures, the politics and practice of charity and welfare, the impact of political conflicts such as war, are questions that cut across several presentations. These are issues that affected human perception and practice during food crises in the past, and they resonate with today’s concerns. The question of “progress” and “improvement” over time is thus a vexed one.

Many of the presentations attempted a synthesis, using evidence from literature and popular culture in different contexts within India and Britain. The history of human perception and representation is as vital as recovering data on individual crises. Local perspectives emerged as a particular priority – discussions of “global” crises can often displace local concerns in the human history of food security. How do we balance them? Geographical specifics, conditions of travel, networks of people, roads, and trades, ecologies and uses of rivers, popular idioms and landmarks, the agency of popular protest against state-led measures, the politics and practice of charity and welfare, the impact of political conflicts such as war, are questions that cut across several presentations. These are issues that affected human perception and practice during food crises in the past, and they resonate with today’s concerns. The question of “progress” and “improvement” over time is thus a vexed one.

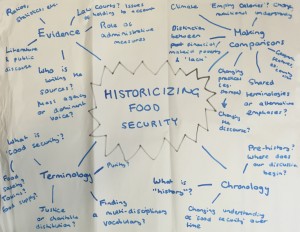

The workshop ended with presentations about the web-database our Famine and Dearth project team are building. These presentations showed how the rapidly transforming field of the digital humanities can assist with food security research and its communication. We targeted our group discussions at methodology and dissemination. Participants were asked to outline issues of method, research questions, and wider engagement strategies that the project team might try to draw into the web-database and project development as a whole. Groups were asked to put down their discussion points on a poster or chart. These formative outcomes can be seen here, and many of the key points raised are being discussed further on our project wiki. We decided that setting up this blog would be a good way to continue our discussions and share our findings more widely.

The workshop ended with presentations about the web-database our Famine and Dearth project team are building. These presentations showed how the rapidly transforming field of the digital humanities can assist with food security research and its communication. We targeted our group discussions at methodology and dissemination. Participants were asked to outline issues of method, research questions, and wider engagement strategies that the project team might try to draw into the web-database and project development as a whole. Groups were asked to put down their discussion points on a poster or chart. These formative outcomes can be seen here, and many of the key points raised are being discussed further on our project wiki. We decided that setting up this blog would be a good way to continue our discussions and share our findings more widely.

Many thanks to the workshop participants for joining our team and for their enthusiastic, vital contributions – and to our Project Partner the Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment at Oxford University for their brilliant support. We welcome suggestions, comments, queries, and blog post submissions from all readers of this blog, of any profession or discipline.

Ayesha Mukherjee