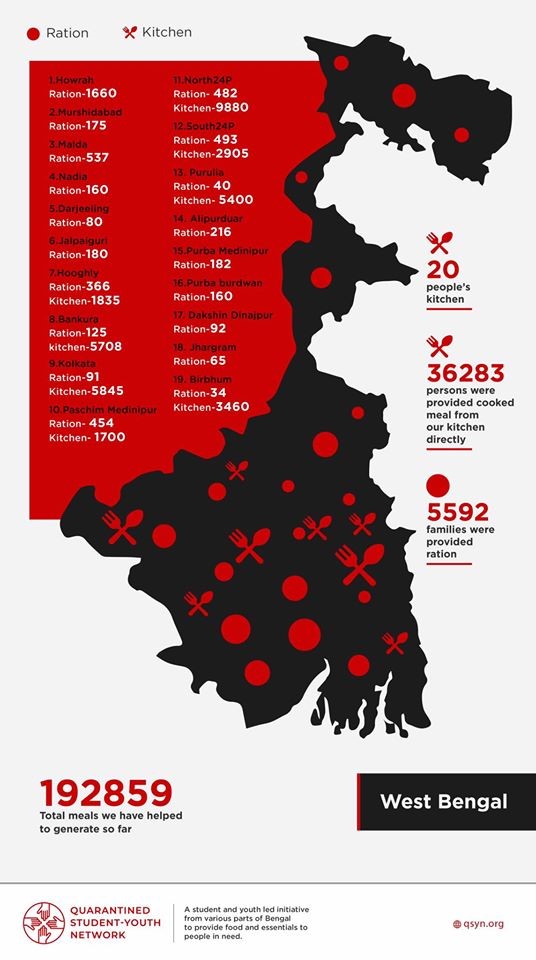

Hunter, Campbell, and the politics of archiving famine

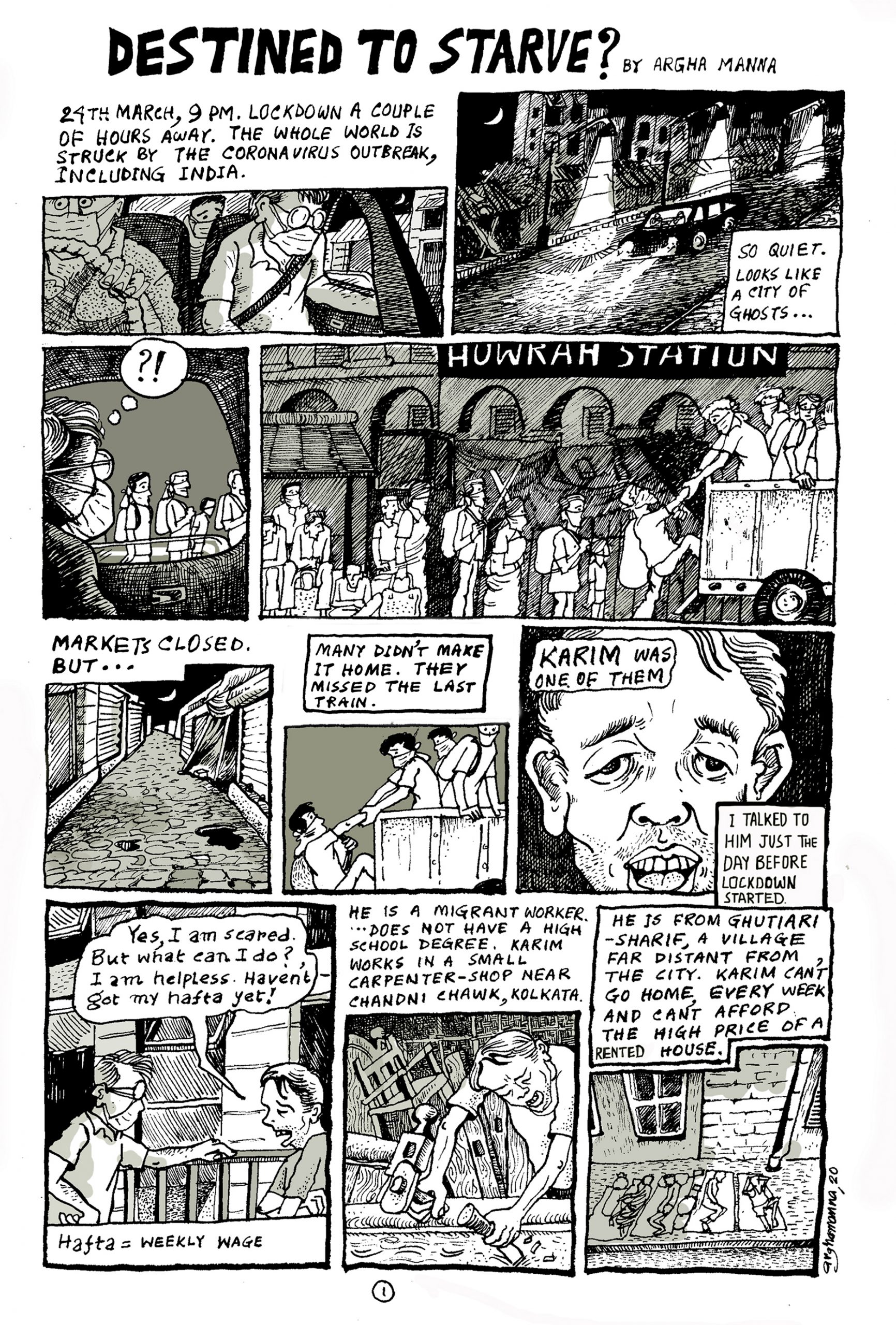

By Ayesha Mukherjee, with original illustrations by Argha Manna

This blog article is jointly published with the Untold Lives Blog, British Library

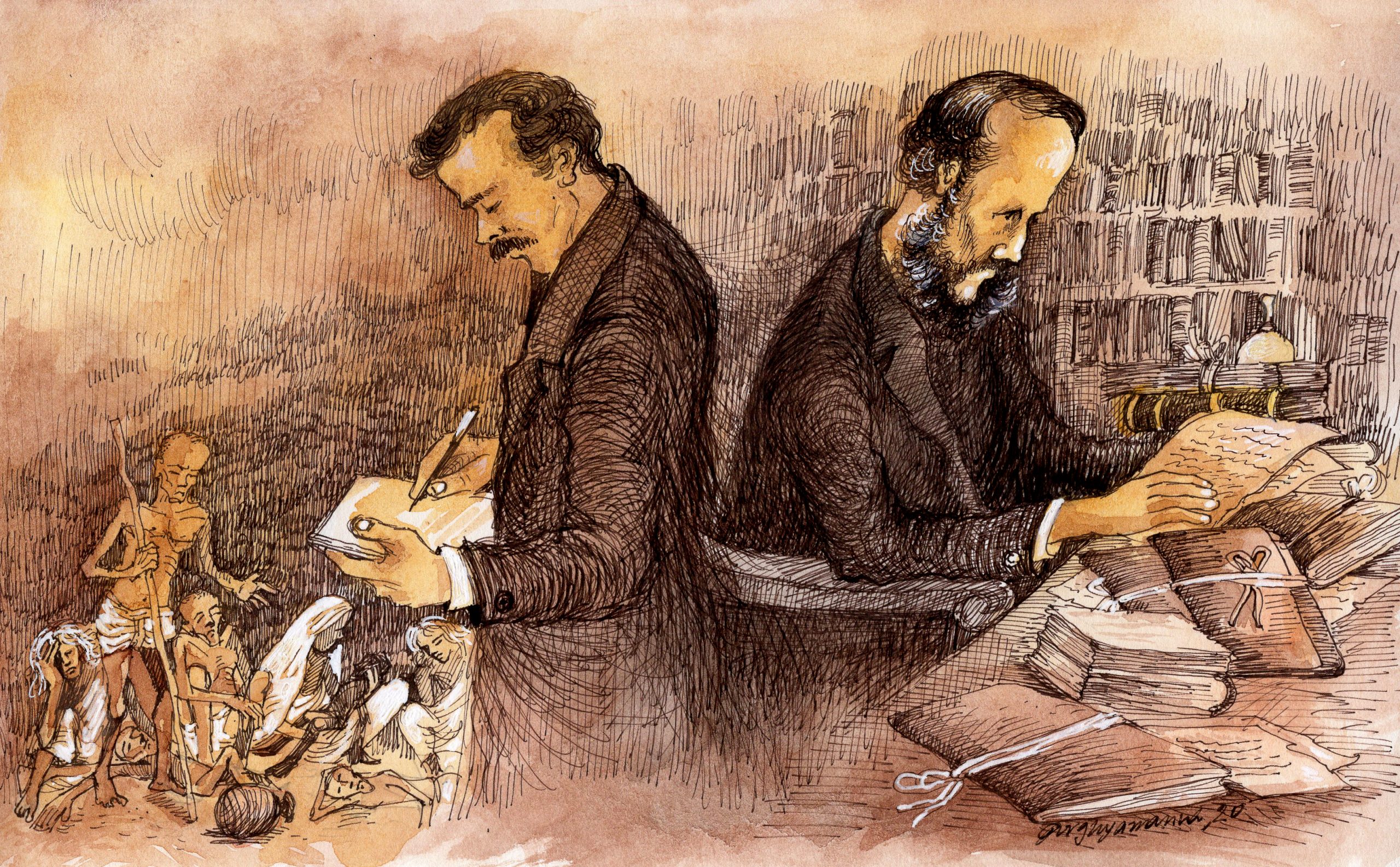

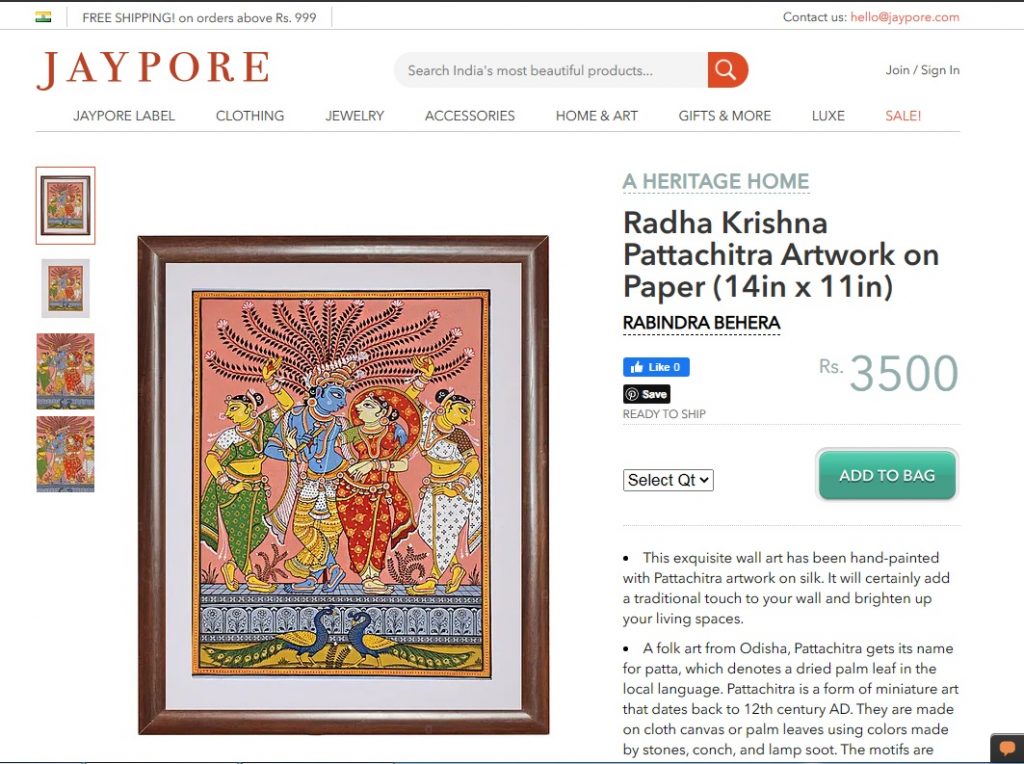

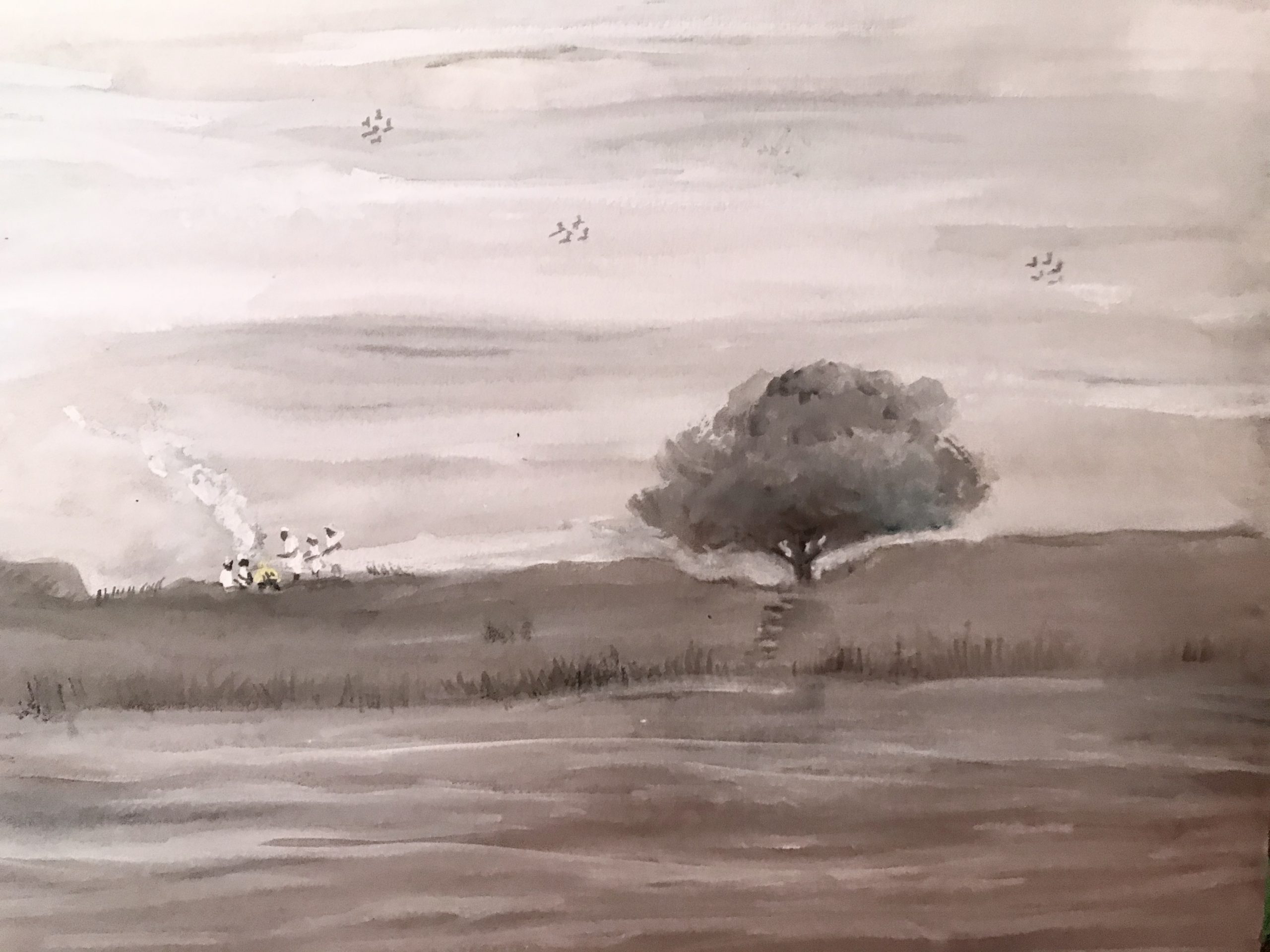

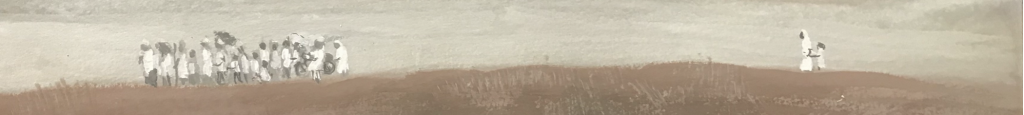

William Hunter and his family travel to Midnapur during the Orissa famine of 1866. Artist: © Argha Manna

In the suffocating heat and violent downpours of early August, 1866, Sir William Hunter, his wife, infant son, and a Portuguese nurse, journeyed to Midnapur, in Bengal, where Hunter had been appointed Inspector of Schools for the South-Western Division. They travelled by road in their victoria driven by Hunter himself. The carriage and horses were crammed on a ferry by which means they crossed the torrential river Damodar. The crossing took 14 hours, and Hunter drove on until the route was cut off by a chasm created by the floods. Horses unhitched, the carriage was dragged down the bank to the other side of the chasm. They reached a rest house which offered little provision. They travelled again, until, hungry and exhausted, they finally arrived at their destination. Hunter then left at once to survey the area as the government was anxious to learn about the effect of the Orissa famine on schools in neighbouring districts. To his horror, he found Bishnupur, the ancient capital of Birbhum, a “city of paupers,” as he noted in his letter to the Director of Public Instruction. The famine relief operations were disrupted by a cholera outbreak. At his own expense, Hunter set up a temporary orphanage for starving children who roamed the streets, feeding on worms and snails (Skrine, pp. 113-15; Hunter, Annals, pp. 53-4).

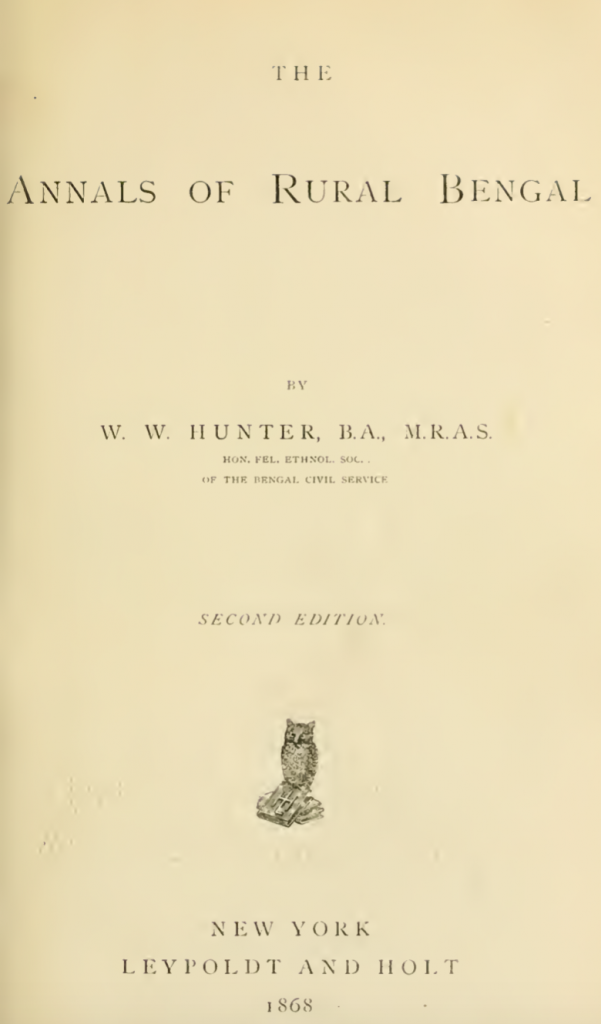

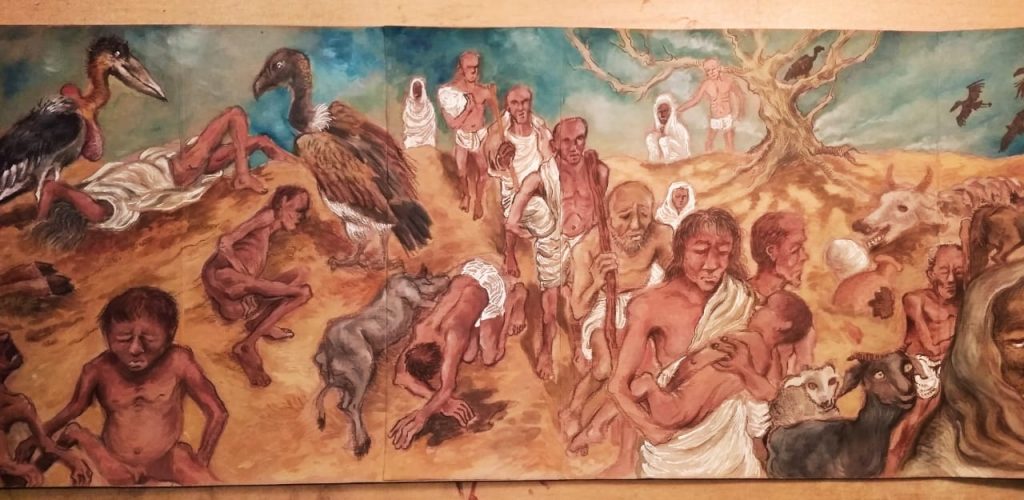

The author of The Annals of Bengal (1867, repr. 1868) – a text often mined for information on the notorious famines in Orissa (1866) and in Bengal (1769-70) – was not simply an excavator of archives. An aspect of his life not often told seems to be epitomised by this stark physical encounter with famine-affected areas, which officers like Hunter (and their families) could not avoid. For Hunter, writing the famous Annals was punctuated by such experiences, as he developed his comparative analytical methods, placing side by side archival findings which allowed him to reconstruct the 1770 Bengal famine, and his immediate knowledge of the Orissa famine a century later. These two famines are infamous events in the history of British administration of the Bengal Presidency. The first resulted in the loss of 10 million lives, and yet the East India Company’s revenue increased in that famine year; during the second, 200 million pounds of rice were exported to Britain while a million starved to death in Orissa (Hunter, Annals, p.56; Naoroji, pp.627-8). Hunter’s analytical method relied on recovering local ecology, history, and demography, loosely modelled on the English annals of parishes. As Hunter wrote to Cecil Beadon in 1868, “My business is with the people” – a rather risky remark perhaps in an epistle to the former lieutenant-governor of Bengal, recently deposed for his mishandling of the Orissa famine and scant attention to the suffering of “the people”. Moreover, Hunter’s approach was analogical, comparing not only past and present famines, but British and Indian models of record keeping; and, finally, it was predictive. Hunter believed that better administration and prevention of future famines were possible through historically informed reflection on current experience.

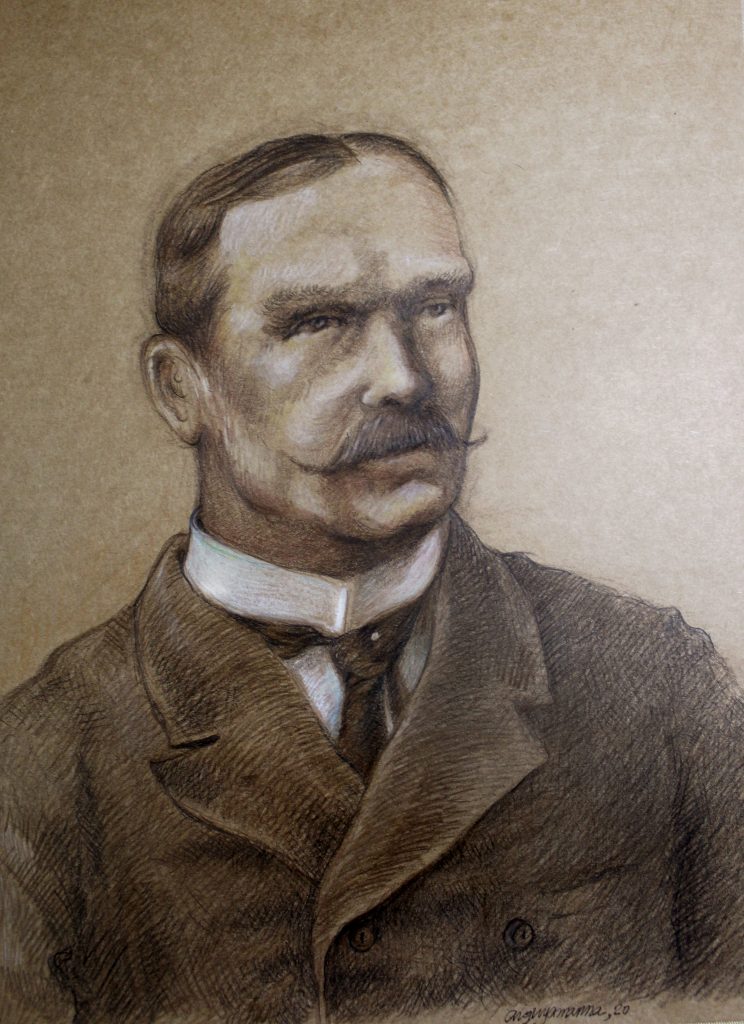

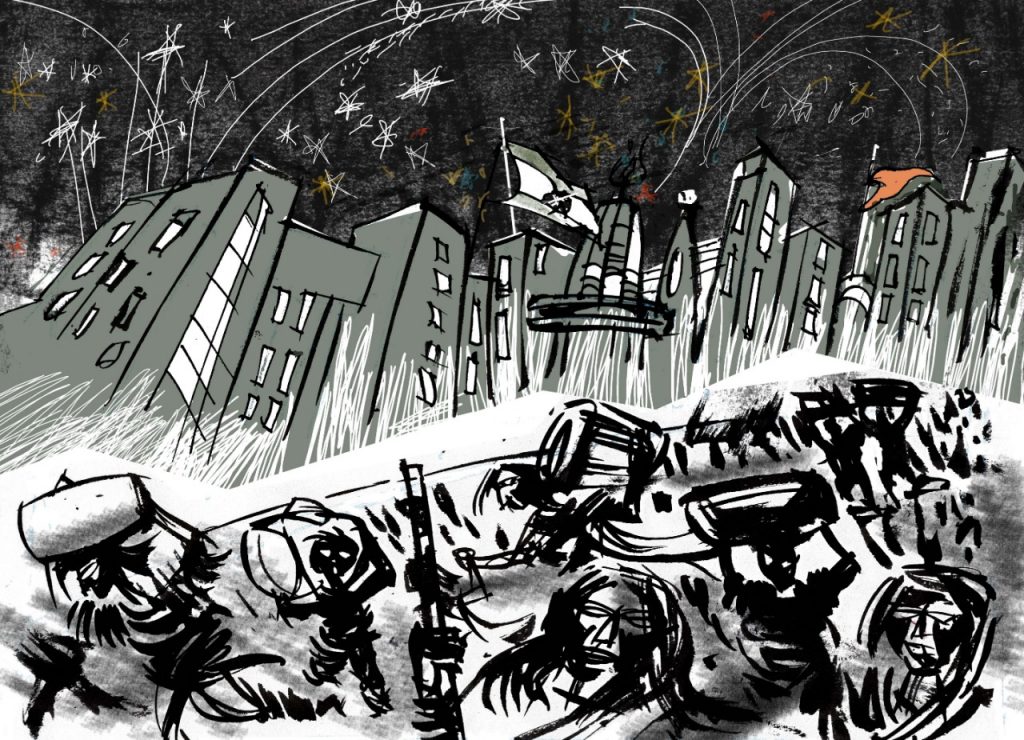

Portrait of Sir George Campbell. Artist: © Argha Manna

Another figure, who has shaped interpretations of both the Orissa and Bengal famines, is Sir George Campbell. He presided over the 1866 Famine Commission and travelled through famine–affected districts of Orissa to gather information. His “Memoir” on the 1770 famine was published in 1867 as part of a “Further Report” (part 4) on the famines of 1866 in Bengal and Orissa, and reprinted by J.G. Geddes in the selection of official documents published in 1874 because “the original edition [was] scarce”. In early 1867, the Commission’s report was published in two large printed folio volumes, and Campbell, upon his return to England in the spring, was asked to examine the India Office records for information on former Indian famines and the “lessons to be derived from them” (Campbell, Indian Memoirs, vol.2, p.130). The famine “Memoir” was the supplementary report that resulted from this endeavour. Campbell, one of the “Punjab school” of British Indian administrators, closely engaged with agrarian questions and the “welfare of the masses”, was a longtime campaigner for the protection of tenants’ rights. The main recommendations of his report – secure tenures for cultivators, more expenditure on irrigation, and improvement of transport and communications networks – were based on a three-way comparison of the famines of 1770 (Bengal), 1783 (North West Provinces, Oudh, Punjab), and 1866 (Orissa).

It is worth noting that Hunter and Campbell were simultaneously active in compiling and analysing records of the 1770 Bengal famine at a time when the colonial government was engaged in controversial debates about its policies and practices of record keeping and publication. This brings a different perspective to the history of the famine, for their evolving approaches to famine records were closely tied to wider political arguments regarding archival preservation, and its relationship with power and governance. In the 1860s, after lengthy debates with the Records Committee (a newly formed advisory body) two opposing models of archival organisation emerged (Bhattacharya, pp.52-90). The government favoured the cheaper option of decentralised and departmentally governed preservation, proposed selective publication of records, with a policy of limited access based on bureaucratic privilege – a model designed to make archiving an utilitarian and instrumental endeavour for the purpose of governance. The other model (vigorously argued by Records Committee members like James Long and J.T. Wheeler) recommended the creation of a centralised muniments room to support permanent public access for the advancement of historical knowledge (Wheeler, 1862). This also raised the rather tricky question of selection – what records might be deemed valuable enough to preserve, while “useless” records were destroyed? The answers remained nebulous in the debates, and the ambivalence is relevant for famine history.

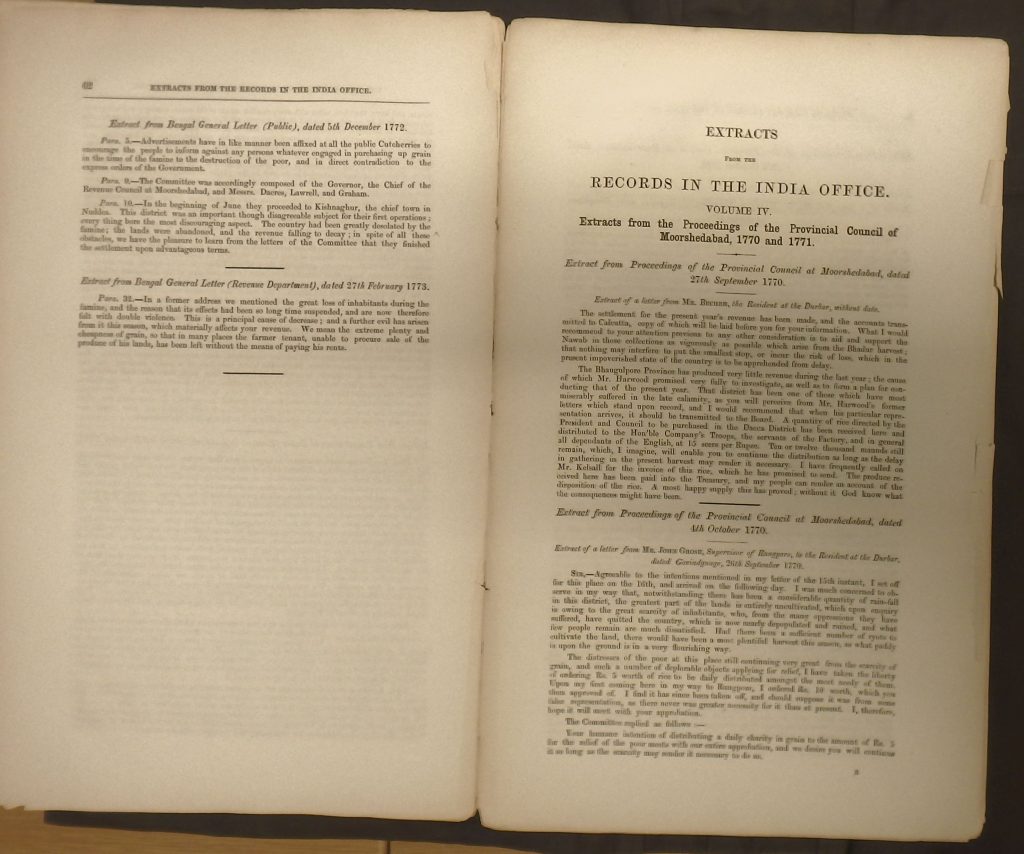

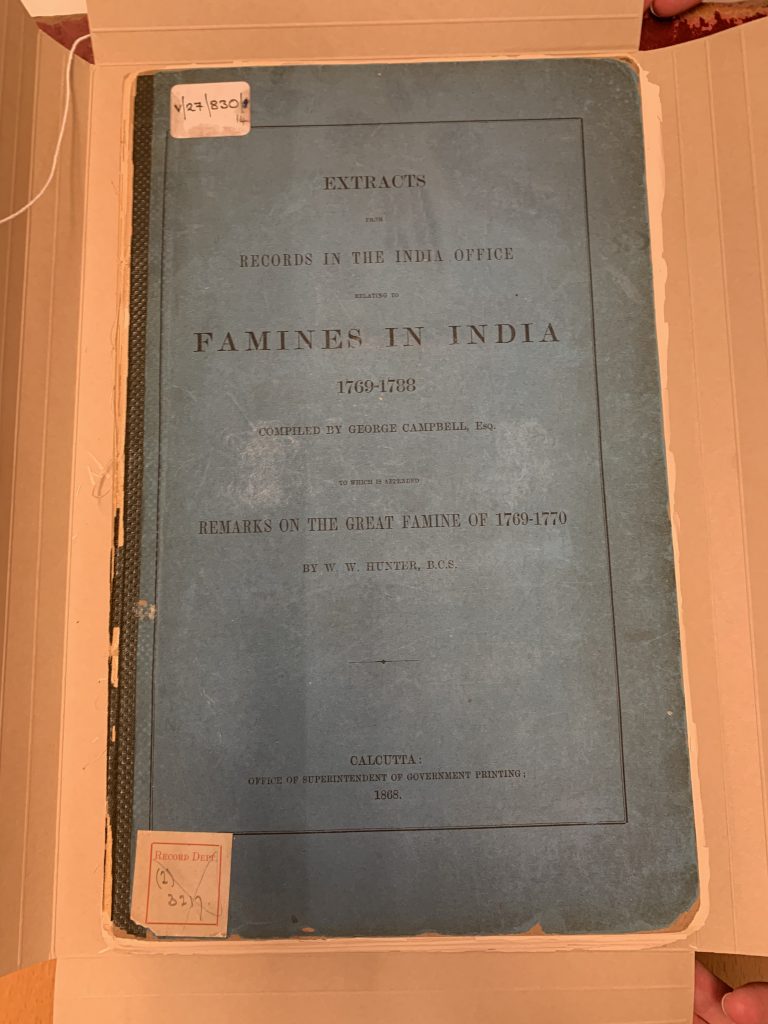

A slim, unassuming, and little-known official publication consciously drew the work of Hunter and Campbell together in 1868, precisely when debates about record keeping and publishing came to a head. The volume was published in Calcutta from the Office of the Superintendent of Government Printing, a position newly formed in 1863 to oversee the transition to a Central Press for official publications (This marked an odd moment in government policy, when a decentralised model was preferred for record preservation, while printing practices were being actively centralised). What seems to be the only extant copy, considerably fragile, is held by the British Library (IOR: V/27/830/14). As the title page asserts, this is a collection of extracts from the India Office records on “Famines in India, 1769-1788”, compiled by George Campbell, probably for the purpose of writing his supplementary report after the Orissa famine. But to it is appended, “Remarks on the Great Famine of 1769-70” by William Hunter. Although the compiled records overlap with the better known texts of the Annals and the “Memoirs”, this is a significant volume for a number of reasons. It brings out the subtly differentiated positions of Hunter and Campbell on the 1770 famine, and on the “usefulness” of historical records. It demonstrates that the polemics of record selection and preservation impacted upon the interpretations of famine policy and history. It allows us to trace (and understand the value of tracing) a textual history of imperial records of famines through a specific case.

Title page of Hunter’s Annals, 1868. Source: University of California Libraries, Internet Archive.

This calls for a more extensive academic study, but I will highlight here a few key points that come up if we compare Campbell’s selection of extracts published here with Hunter’s selection of sources appended to his Annals. Campbell confined himself to the India Office Records, prioritised extracts, and arranged them chronologically. Hunter’s combination of India Office and local records, on the other hand, were organised to show the different emphases of different types of record. Campbell admitted in his famine memoir, “It has only been possible by completely sifting the general records to pick out here and there the passages that bear on the calamity [1770 Bengal famine]. The result is not to give us its history in any great detail, but I trust that enough has been gathered to put us in possession of its general character.” (Geddes, p.409) For Hunter’s purpose – which was not only to offer “lessons” in governance – nuanced historical detail found in records in English, Bengali, and Persian, from a wide range of sources, proved valuable: the India Office in London; the Calcutta offices; revenue and judicial records from the courts and offices of Birbhum, Burdwan, and Bankura; domestic archives of rajahs and families in Birbhum and Bishnupur; tracts and newspapers in Joykrishna Mukherjee’s Uttarpara collection; memorial reconstructions in interviews conducted by Hunter, and local legends gathered from tribes such as the Santhals. Hunter’s approach was rather more peripatetic than being confined to the London office! Working in remote district offices, he described the isolation of this labour which produced “a work written in the jungle, eight thousand miles distant from European libraries.” (Hunter, History, p.1) He published a selection of varied sources in appendices to the Annals. The agenda of historical recovery was evidently wider than Campbell’s emphasis on discovering the “cause” of the 1770 famine, which, Campbell urged, was drought, not inundation. On the subject of revenue remission during famine years, we often see Hunter and Campbell making almost identical selections from the India Office records; but in his additional annotations, Hunter critically examines claims in these records of the extent of remission. Their regional focus also differs. Hunter’s aim was to write a local history of Bengal; while Campbell highlights the frequently ignored impact of the famine on Bihar.

In 1874, Campbell took over as Lieutenant Governor of Bengal, and the reprinting of his famine memoir in Geddes was partly designed, I think, to underline this change of governance. Although Campbell had a reputation of being a more radical figure than Hunter, who is considered to have defined a colonial agenda for historical research, the former’s approach to record selection and analysis of the famine of 1769-70 appears far more aligned with the government’s proposition that the ultimate end of record-keeping was colonial governance. This seems to be where the two men subtly differed. While Hunter’s recommendations to the government in 1872 supported decentralised record-keeping in each department, with regard to selection and publication he was on a very different page. He proposed a careful system of central and local cross-checking before any records were destroyed and laid a balance of emphasis on Indian records as well as English ones. He recommended that selections should be made “by a two-fold organisation, acting partly in England and partly here [India].” (Hunter to Howell, Nov. 1871, NAI) The British government, on the other hand, were entirely blunt in their assertion that “the publication of old records is a matter of political [rather than historical] importance”. The selections, they hoped, “would do much to prevent misconstruction of the policy and motives of Indian Government.” (Govt. to Argyll, Dec. 1872, NAI) Ironically, many of the policies of governance they may have sought to defend were policies that Campbell the new lieutenant-governor, with his reputation for “radical” politics and insistence on tenancy reforms, sought to change.

Such complexities in the characters, motivations, and official functions or reputations of Campbell and Hunter, which shifted with movements in regional governance and colonial politics, show that neither figure quite fits the clichés of the colonial bureaucrat or the radical protester. Their analyses of famines transformed across time, and their texts bear these marks. The intertextuality of this writing, its political impulses, its investment in very particular processes (and policies) of compilation and archiving can shed new light on the famine histories these figures are known for recovering.

******

Further Reading

Bhattacharya, Sabyasachi (2019). Archiving the British Raj: History of the Archival Policy of the Government of India, with Selected Documents, 1858-1947. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Campbell, George (1893). Memoirs of My Indian Career. 2 vols. London: Macmillan and Co.

Campbell, George, and William Wilson Hunter (1868). Extracts from Records in the India Office Relating to Famines in India, 1769-1788, compiled by George Campbell, to which is appended Remarks on the Great Famine of 1769-1770, by W.W. Hunter. Calcutta: Office of the Superintendent of Government Printing. British Library, IOR: V/27/830/14 .

Geddes, J.C. (Jan 1874). Administrative Experience Recorded in Former Famines. Calcutta: E Bengal Secretariat Press.

Government of India to Argyll, 1872, Home Department, Public Branch, No.95, National Archives of India (NAI) .

Hunter, William Wilson (1867, second ed. 1868). The Annals of Rural Bengal. London: Smith, Elder and Co. New York: Leypoldt and Holt.

Hunter, William Wilson (1899, 1900). A History of British India. 2 vols. London: Longmans, Green, and Co.

Hunter to Howell, 1871, Home Department, Public Branch, No.3771, 1872, NAI.

Naoroji, Dadabhai (1901). Poverty and Un-British Rule in India. London: Swan Sonnenschein & Co.

Shaw, Graham (1981). Printing in Calcutta to 1800: a description and checklist of printing in late 18th-century Calcutta. London: Bibliographical Society.

Skrine, Francis Henry (1901). Life of Sir William Wilson Hunter. London: Longmans, Green, and Co.

Wheeler, J.T. (1862). “Memorandum on the Records of the Government of India”. Home Department, Public Branch, No.19, 1865, NAI.

******

Acknowledgements: With grateful thanks to Dr Antonia Moon for drawing my attention to IOR: V/27/830/14 and permitting me to view it, and to Professor Swapan Chakravorty for directing me to valuable sources on colonial archiving policies in India.

******

Ayesha Mukherjee is Associate Professor of Early Modern Literature and Culture in the Department of English and Film, College of Humanities, University of Exeter, and the Principal Investigator for the AHRC projects Famine and Dearth in India and Britain, 1550-1800, and Famine Tales from India and Britain.

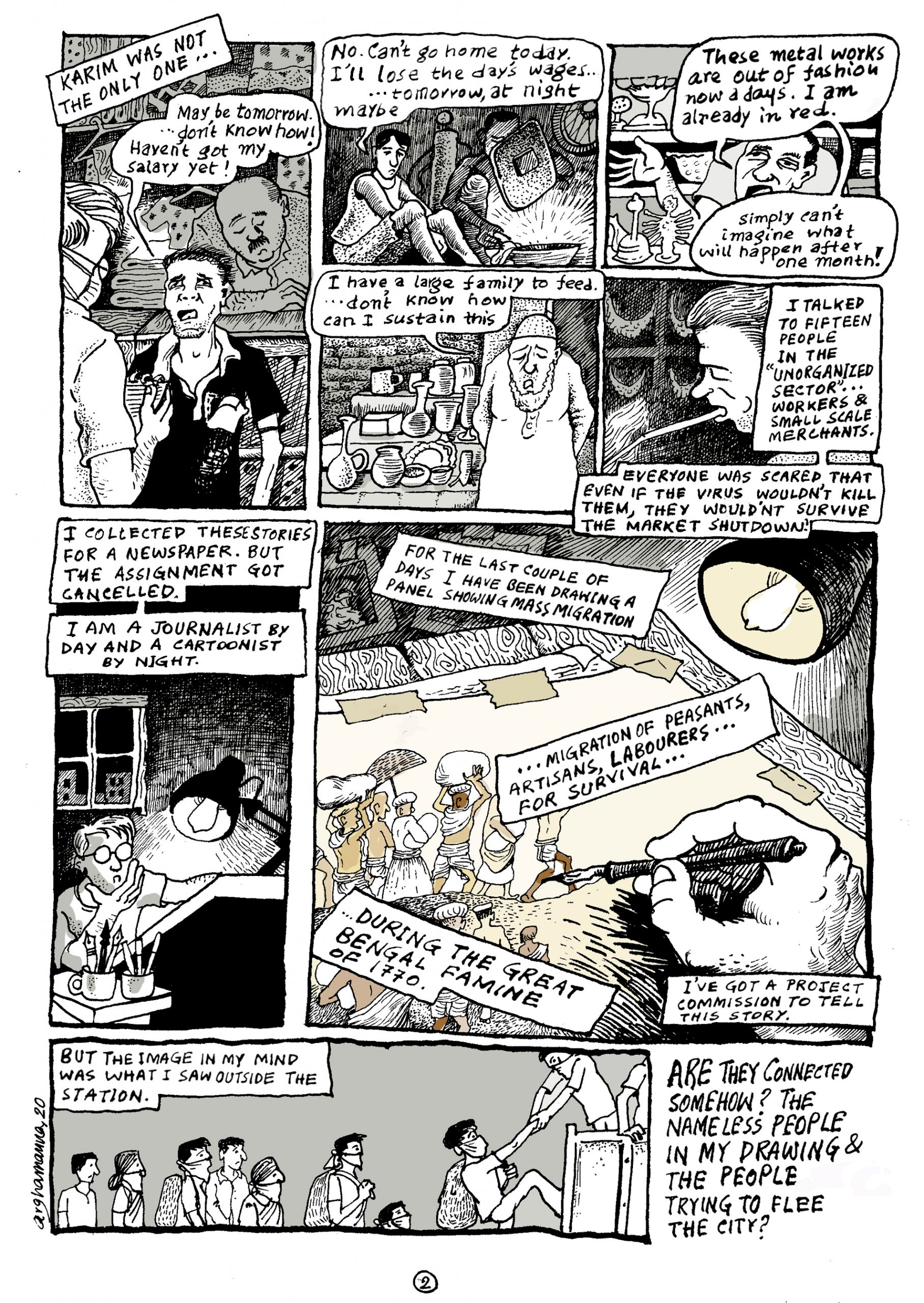

Argha Manna is a graphic artist and journalist based in Calcutta, and is currently creating a graphic narrative of the 1770 Bengal famine for the Famine Tales from India and Britain project.

![Hoe men de Caneel schilt opt Eyland Ceylon [peeling cinnamon in Ceylon], c.1672. By Anonymous (engraver), Johannes Janssonius Waasbergen (publisher)](http://foodsecurity.exeter.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/AMH-7014-KB_Peeling_cinnamon_on_Ceylon-195x300.jpg)

![Soc[1].Ant 1](http://foodsecurity.exeter.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Soc1.Ant-1-153x300.jpg)