Recreating Sir Hugh Platt’s Parsnip Cake

Lily Long

Famine “remedies” to food shortage

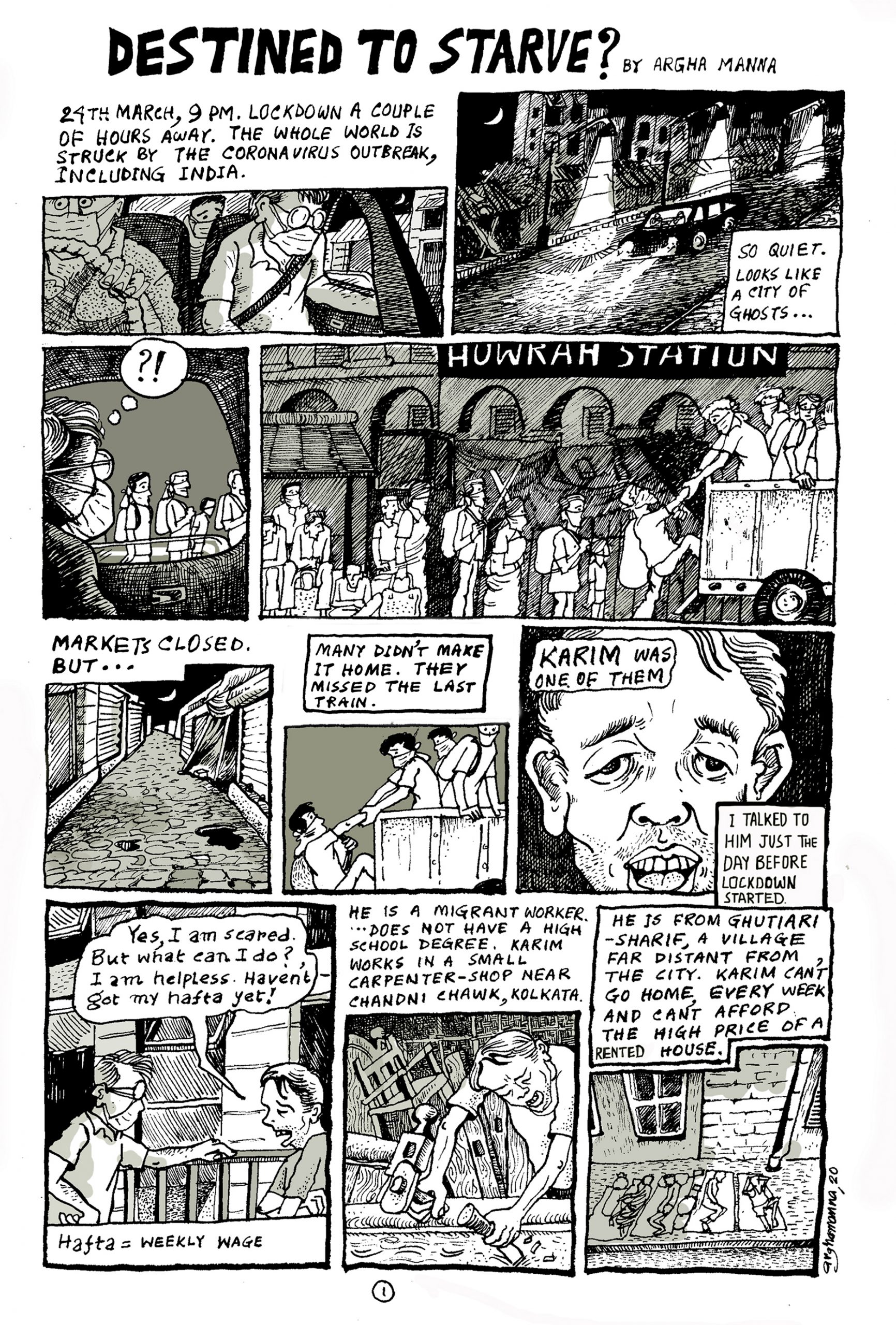

The newly released tale, Shekkhopir-deshe Durbhikkho (Famine in Shakespeare-land), considers one of the worst famines in the history of Renaissance England. In the late-sixteenth century, the English population bore witness to repeated crop failure, outbreaks of disease, declarations of war, a surge in population, as well as sharp price rises. The 1590s were especially desolate, with four consecutive years (1594-97) of harvest failure. In direct response to this food scarcity, in 1596 Sir Hugh Platt, an early-modern English scientist and writer on agriculture, wrote a manual called Sundrie new and Artificiall remedies against Famine. Platt added recipes for common foodstuffs but with more readily available ingredients in times of shortage; for example, bread could be made “of the rootes of Aaron called cuckowpit”, with Platt’s instructions on how to prepare the roots to make a “most white & pure meale”, substituting wheat flour.

Another notable section is the recipe for “Sweete and delicate cakes made without spice, or Sugar.” Platt gives instructions on how to extract the natural sweetness from “parsnep rootes” to act as a substitute for the extravagant sugar used in cakes. Cakes using root vegetables aren’t uncommon nowadays (carrot cake remains one of my all-time favourite desserts) but I must admit that a parsnip cake seemed to me a strange, yet enticing, substitution.

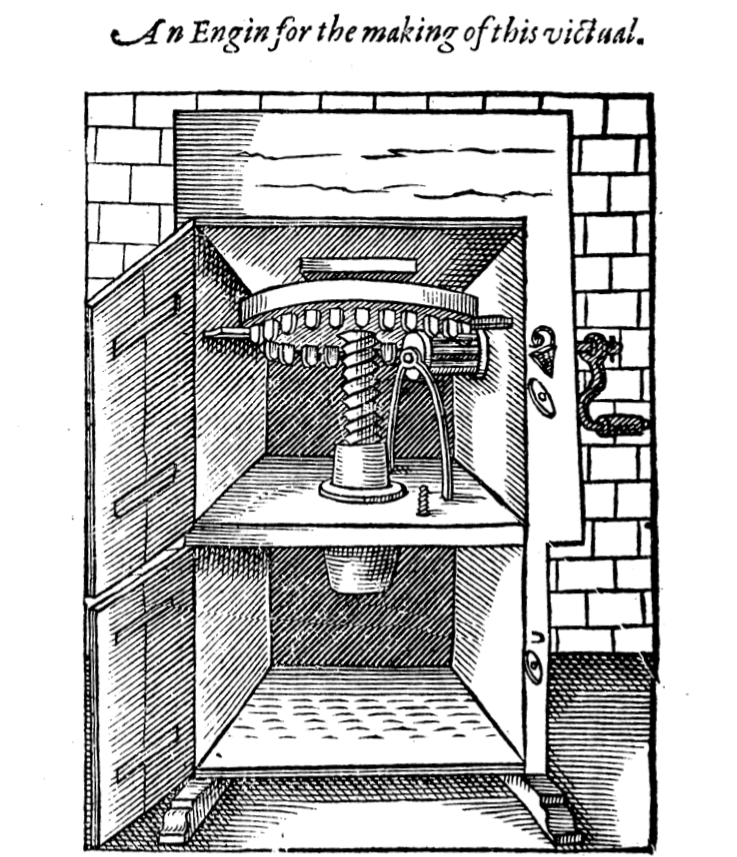

As interns, we are thoroughly encouraged to conduct additional research on the events and tales that the project exhibits, which ultimately led me to consider the possibility of recreating Platt’s recipe in modern times. I wondered whether there was something to be learnt from engaging with the material processes of early modern times. Although I didn’t have access to a “mil” which he advises for grinding the parsnips, I was quite impressed with the finished result despite my adaptations! After all, Hugh Platt himself encouraged the users of his receipt books to adapt if need be.

The process of making the modernised early modern recipe

Firstly, Platt asks us to “[s]lice great and sweete parnsep rootes (such as are not seeded) into thin slices, and having washed & scraped them cleane, dry them, and beat them into a powder.” So, I chopped the parsnips as thin as I could muster, placed them on a baking tray, and then put them in the oven for just over five hours to remove any moisture. By the end, they had completely shrivelled up, unsurprisingly resembling dried banana.

The next step was the hardest. I needed to “beat” the dried parsnip into a powder, but didn’t have any equipment that could suitably achieve this. The closest thing I did have was my mini portable smoothie maker, which, once I put the parsnip pieces in, stopped working. After (too) much deliberation, I then tried to chop up the parsnip as finely as possible, to then put back into the blender, but once again, unsuccessfully! I decided that I would have to stray from Platt’s original vision and put walnut-like chunks of parsnip into the cake mixture.

My chunky parsnip mixture came to 90 grams, and Platt instructs to “knead two partes of fine flower with one part of this pouder”; so, next I added 180 grams of gluten-free flour (as I’m gluten-intolerant) to my bowl. This is where the official famine “remedie” ends, with Platt leaving it up to the reader’s discretion what they have available to add to the cake mixture, saying “[i]t may be made as delicate as you please, by the addition of oyle, butter, sugar, and such like.” For my modern version, I had butter, milk and two eggs at my disposal, and kept adding them to my mixture until a veritable cake batter had formed. I then divided it into individual muffin cases, putting them into the oven at 160 °C for 25 minutes.

The smell in the kitchen was divine, the natural sweetness of the parsnips floating through the air. I tore one open, and I was very pleasantly surprised; a little dry, but I put this more to my shortage of compensating butter and milk. I actually enjoyed the chunks of parsnip, it added a texture similar to that of currants to the cakes.

Cakes and famine?

If I were to make the cakes again, I would attempt to grate and then bake the parsnips to see if that would make a more successful fine powder, closer to that which Platt intended. I would also leave the parsnips for a couple of hours longer, to make sure they had completely dried out. But there is a limit to how close we can get to early modern materiality in modern times. It was still a really interesting prospect to try and recreate this recipe. I was intrigued by the way the idea and experience of “sweet” and “delicate” taste might have changed over time, and the fact that Platt doesn’t set aside the comfort of tasting something pleasant in times of crisis. There seems to be an element of psychosomatic comfort to making “famine food”, and it is not always only about stretching short supplies as far as they will go.

******

Lily Long is a fourth year student of English and French at the University of Exeter. Her interests also extend to cinema, and the researching and archiving of historical material. She has previously worked as an intern on Exeter’s Colloquium on Innovation in Modern Languages. Lily is contributing to the creation of digital outputs for the Famine Tales project, including the markup of texts and the creation and curation of digital exhibitions.