Community Kitchen Initiatives in UK and India

Towards a transformative politics during the time of Covid-19

By Rishika Mukhopadhyay

From BBC News, 15 March, 2020

The week before the official lockdown in the UK, we knew something ominous was coming because the supermarket shelves were emptying fast. The first advice I had was to secure grocery to survive for a few weeks. Within a few days, the shelves were replenished and there was no shortage of food in my life here. A strange calmness engulfed me in this little town of South West England. Sitting in the comfort of the four walls of my room in Exeter, I hardly realised how Covid-19 ravaged people’s lives elsewhere. I was allowed to go out once a day for exercise, to use that time of walking attentively and mindfully, soak in the nature around us. My well-wishers were concerned about my health and wellbeing. I focused my energy on creating ideal working conditions, as ‘work from home’ became the new norm. It was alright, until one day when I encountered the image of Indian migrants’ ‘long march home’.

From Times of India, 27 March, 2020

My reality transformed drastically as a virus-hit world once again exposed glaring inequalities and showed how few of us are granted privileges. From the very beginning, every government decision designed to prevent the spread of this virus, in the UK and India, was taken keeping in mind people like us: who have a safe home to stay in, endless water supply to wash their hands, whose vocabulary includes “hand sanitiser”, and who can afford to think about “social distancing” while working from home! I felt terribly unsettled by these pandemic mitigation policies where a whole section of the vulnerable population was rendered silent and invisible unless they decided to walk thousands of kilometres to reach their home!

It is not the virus alone that is a threat. Extreme hunger and starvation are threatening the lives of millions of people. The world food program (WFP) has already estimated that 265 million people are suffering from acute food shortage due to Covid-19. The chief of the UN food relief agency cautioned that famine can devastate 30 countries in the developing world. The picture is bleak in countries like the UK as well. The Food Foundation report reveals that during the first three weeks of the lockdown in the UK, three million people were hungry. In these trying times, food insecurity is not limited to those who have lost jobs and are therefore economically distressed. Rather a significant section of our demography, including families with children who used to get free school meals and the aged population who are alone, have been affected severely. In India, migrant workers who are daily wage earners, waste-pickers, casual workers in small enterprises, hawkers, and artisans are at the receiving end of this humanitarian and food crisis. Administrative effort to reach people who are going through deprivation and starvation with food and ration is scant. Reporters have found out that children are eating grass in some parts of the country after enduring extreme hunger for days.

From National Herald, 27 March, 2020

Nevertheless, these are times when people often come together to foster a sense of solidarity, compassion and a hopeful future. Soon, I heard some friends and teachers from my previous University in Delhi had set up a community kitchen to distribute cooked food to various industrial clusters in Delhi, where migrant workers now live a precarious life without income and food. The Worker’s Dhaba was not the only one; across the country many citizen’s initiatives started to consolidate efforts and reach people who are in dire need. These active interventions by ordinary citizens give me optimism and strength amidst this global pandemic. I will talk about four such initiatives, two from India and two from Exeter, to understand how citizen’s actions can lead to a transformative politics.

Workers’ Dhaba, New Delhi, India

For over a month Workers’ Dhaba, run by three cooks and volunteers is regularly cooking and distributing meals twice a day to about 2000 people across Delhi. It came together under the banner of Citizen’s Collective for Humanitarian Relief (CCHR). The Center for Education and Communication (CEC) helps them with operational guidance and technological outreach. Many civil society organisations, like press club, and café lota, are partnering with them to distribute food widely. They are also providing dry rations, milk, and baby powder in slums, settler camps, and squatters. In the true spirit of community collaboration, a second kitchen has been opened away from the university space. The idea was to localise food production and include the community. Here, community members of two slums are cooking together and distributing food to other areas, showing extraordinary resilience, support, and cooperation. Praveen, the researcher who was responsible for distributing food in this area and later made the collaboration possible told me:

“We aren’t doing any charity or philanthropy which is premised on the inherent structure of hierarchy and power. We are all in this together! The collaboration was a result of community feeling. With a little help and support, people have immense potential to rebuild their lives. It was amazing to see people from both the Jhuggis coming together and volunteer themselves for cooking and distribution.”

The effort of decentralisation and moving into more neighbourhood-based kitchen initiatives run by local communities is a prominent future plan of this collective.

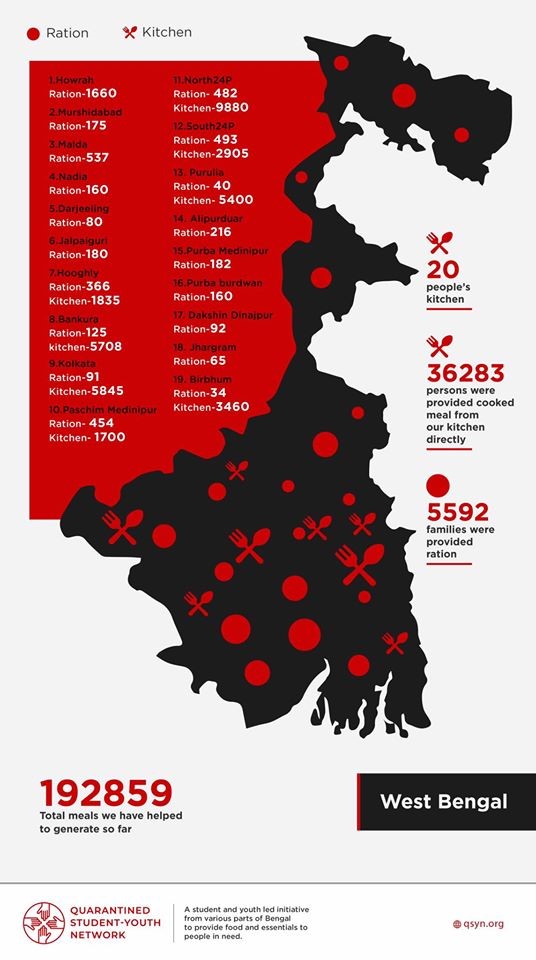

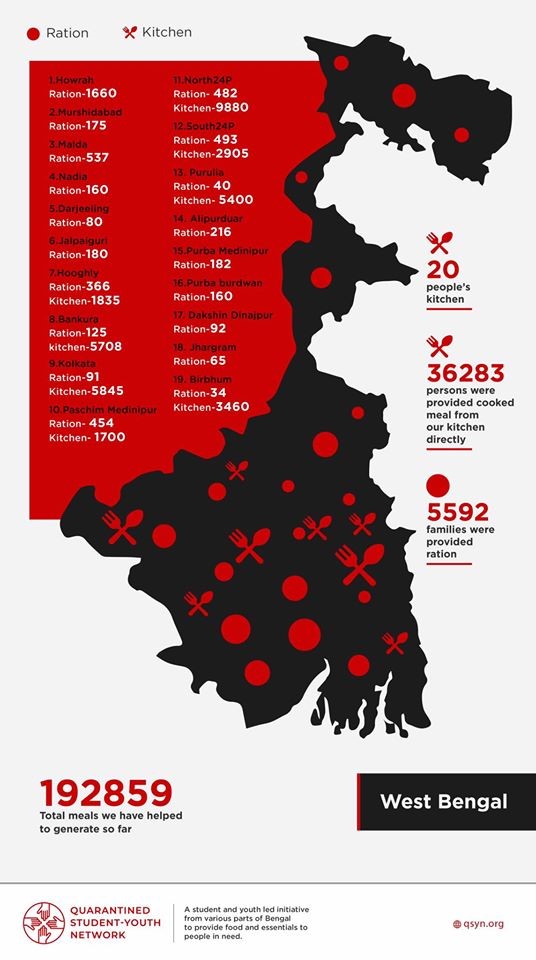

Quarantined Student-Youth Network, Kolkata, India

Another friend from Kolkata shared with me how they have built the Quarantined Student-Youth Network run by students and alumni from universities in West Bengal. Koumi said, “We are now joined by so many who believe in the principle of physical distance and social solidarity. We work in parts of West Bengal and some areas in Delhi, Mumbai, and Hyderabad.” They joined hands when they realised how inadequate the response of the State has been in identifying, locating, and reaching out to the affected population. Their operational framework enables people to make use of digital technology efficiently during lockdown by identifying their location on the map where relief from the Public Distribution System (PDS) hasn’t reached. Each local district volunteer then verifies the complaint and reaches out to people in that area by delivering ration or other requirements. For homeless migrants living in temporary shelters and pavement dwellers in the city, delivering cooked food is the only measure, whereas in villages they run People’s Kitchen. Wherever needed, they deliver soap, sanitary napkins, masks, sanitiser and medicine. Similar to the idea of the Delhi network, this group firmly believes that they are neither running a charity nor acting as benefactors. Debojit, another member of this network, says passionately:

“It must be noted, those we are trying to assist continue to further our society and civilisation without receiving adequate compensation for their labour. Thus, this solidarity is their right, it’s not a donation.”

Treating the vulnerable population with respect and dignity is one of their guiding values; another is their outreach to remote corners of Bengal, not just limited to the state capital, Kolkata. The helping hand of the local community – farmers, fishermen, and workers from all sorts of backgrounds – have helped to strengthen their feeling of being a commune. Through non-monetary exchanges, such as receiving unsold vegetables from farmers in exchange for rice, pulses, or fish, and forming cooperatives, this student initiative carves out a space of hope for an alternative politics.

St Thomas Food Fight, Exeter, UK

Food Donated to St. Thomas Food Fight (Source: their Facebook page)

In Exeter, quite a few organisations are working to provide free cooked meals. I have spoken to two of them to understand how, in the UK, issues of starvation, hunger, and food insecurity affect people’s lives. A member of the St. Thomas Food Fight group, Alison, told me why they were motivated to start this initiative:

“A few of us started thinking about food poverty some time ago. Students from the University of Exeter started Exeter Food Fight and gave out free hot food and drinks in the High Street. Out of that came St Thomas Food Fight. We are motivated by compassion and a desire to see everyone fed and looked after.”

Exeter Food Fight is a grassroots community group committed to raising awareness regarding issues like poverty, sexism, and racism. They reach out to not only the homeless in the city but also the elderly, disabled, lonely, young families, or those affected by substance abuse and mental health problems. During the lockdown, they started by dropping off hot food for takeaway in paper carrier bags outside Natwest Bank on Cowick Street. The initiative expanded when a charity St. Petrocks asked them to provide cooked food for 33 homeless people during the lockdown. They also get requests from organisations like CoLab Exeter to prepare meals for the vulnerable being shielded. They cook for 30 people in the community who are in food poverty or unable to cook for themselves regularly. Apart from the Devon County Council Covid Response fund, they have immense support from the local community, who bring them packaging, donate vegetables, or cook a one-time hot meal. A cycling activity group FREEMOVEMENT help them with deliveries. An organic farm Shillingford offers them vegetables from their local firm, and Exeter Food Action provide a wide range of food, including rice, pasta, and beans.

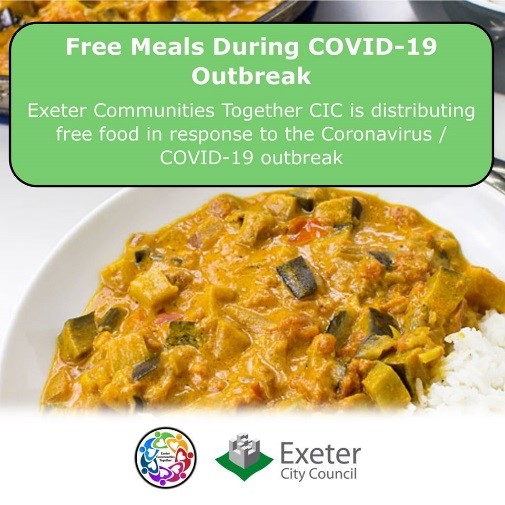

Exeter Communities Together CIC, Exeter, UK

Exeter Communities Together CIC runs a Coronavirus Hardship Relief Project during lockdown from Exwick Community Centre. They receive support from Exeter City Council, Devon County Council, and Morrisons of Crediton, along with public donations. They not only help the elderly vulnerable population by giving food to residential care homes but also reach out to frontline workers such as NHS caregivers and the police, or anyone who is struggling financially. This organisation was established to give Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic (BAME) people in the city greater voice. They translate important information on self-isolation and social distancing for wider circulation. Anyone in Exeter can ask for their support for assistance in shopping for essentials and medicines.

There are many inspiring stories – from women organising themselves from their homes in London to a couple turning their closed pub into a community kitchen and food bank in Melling – in the UK. In the four examples featured above from India and the UK, despite the varying scale, intensity, and nature of organisation, one common factor connects them. That is, their commitment towards a transformative and emancipatory politics through democratic mobilisation and collaboration. With the rise of divisive politics all over the world, this pandemic has brought many people closer and fostered cooperation.

Detail of sketch by Debkumar Mitra, for Famine Tales from India and Britain

Arundhati Roy has written how, historically, pandemics have been a portal to break free from the old world of lies, prejudices, greed, exploitation, hatred and violence and bravely imagine a hopeful future. We must think about what we can change when things go back to “normal.” The pause this has brought to our lives should lead us all to reimagine and rethink our everyday actions for a sustainable and just world. We have been hearing around us a call for reworlding. We cannot go back to “normal” as it was, because the way we led our lives, by exploiting and abusing nature for the benefit of a few global corporations and their political corroborators, cannot be our normal. A capitalist production regime for the interest of the few and its subsequent unhinged growth narrative must be challenged now by adopting a language and practice of meaningful living. On the one hand we need to strengthen the demand for Universal Basic Income, for labour rights, and make our governments accountable for investing more in the domains of food security, health care, housing, and accessible education for public welfare. On the other hand, we need to reorient our own priorities and consumption practices.

The way forward is not only to build networks of care, support, compassion, and solidarity around us and with the non-human world, but also to radically reimagine our future economic practices. The provocation of A Post-Capitalist future, proposed by feminist economic geographers JK Gibson-Graham is not a utopia anymore. Around the world, people are actively participating and creating a vision for another world by building resilient communities interdependent on local resources, away from the global chain of commodity production. Practices of commoning, co-operatives, building solidarity economy and community economy have started. Building a community kitchen during the time of this catastrophe is an extension of this imagination and the alternative politics it embraces. These groups have a clear vision that their work will solidify ethically driven collective efforts for justice and dignity, and embolden an idea of community beyond heteronormative family and kinship structures. To change the abysmal state of the world, we need to reorganise our lives. The possibilities are endless and diverse. It is time to reframe our ontologies of being to build a world we want to live in.

Acknowledgements

I thank my friend Ghee Bowman for directing me towards the Exeter initiatives. Thanks to Mariel for suggesting some of the articles for reading and the postcapitalist summer school in Sydney for inspiring me to think in this direction.

Rishika Mukhopadyay is a final year PhD student in Human Geography at the University of Exeter, UK. She did her Masters and MPhil in Geography from Delhi School of Economics, Delhi University.